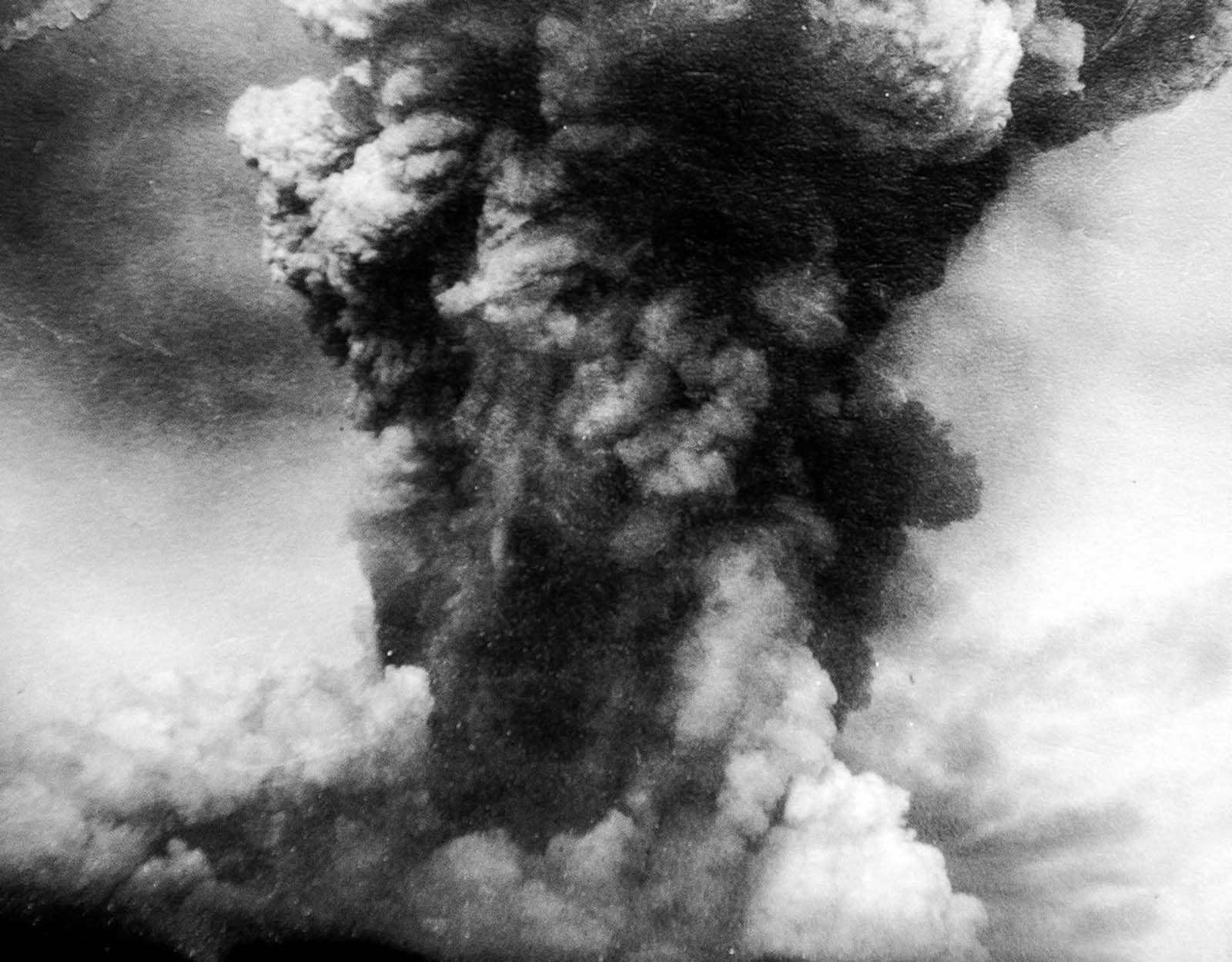

A massive smoke cloud rises into the sky moments after the 2.9 kiloton explosion.

It was a blast heard around the world. News of what happened when two ships collided in the harbour of the historic port city of Halifax, Nova Scotia, on December 6, 1917, made headlines worldwide. In times of war, accidents happened in busy seaports, and life went on. But this time, things were different.

One of the vessels involved in the collision was the SS Imo, a Norwegian war-relief ship. The other was SS Mont-Blanc, a rusting French tramp steamer that was loaded with gunwales with high explosives, almost 3,000 tons of picric acid, TNT, and gun cotton, while piled high on her deck were hundreds of barrels of high-octane benzol fuel.

The Mont-Blanc was a floating bomb. As one veteran Royal Navy officer would later marvel, “I’m surprised that people on the ship didn’t leave in a body when they saw the nature of the cargo she had been ordered to carry”.

The chain of events that put Imo and the Mont-Blanc on a collision course was as improbable as it was bizarre. It defied logic. The weather was clear and mild. The sea was calm. Veteran harbour pilots were guiding each ship. The Two captains involved were experienced mariners.

A view of Dartmouth, looking across the harbor to Halifax. 1900.

The Norwegian ship SS Imo had sailed from the Netherlands en route to New York to take on relief supplies for Belgium, under the command of Haakon From.

The ship arrived in Halifax on 3 December for neutral inspection and spent two days in Bedford Basin awaiting refuelling supplies. Though she had been given clearance to leave the port on 5 December, Imo’s departure was delayed because her coal load did not arrive until late that afternoon.

The French cargo ship SS Mont-Blanc arrived from New York late on 5 December, under the command of Aimé Le Medec. He intended to join a slow convoy gathering in Bedford Basin readying to depart for Europe but was too late to enter the harbour before the nets were raised.

Ships carrying dangerous cargo were not allowed into the harbour before the war, but the risks posed by German submarines had resulted in a relaxation of regulations.

Navigating into or out of Bedford Basin required passage through a strait called the Narrows. Ships were expected to keep close to the side of the channel situated on their starboard (“right”), and pass oncoming vessels “port to port”, that is to keep them on their “left” side. Ships were restricted to a speed of 5 knots (9.3 km/h; 5.8 mph) within the harbour.

Shortly before 9:00 am the Imo, headed out of Halifax Harbour and found itself on a collision course with the Mont-Blanc. After exchanging warning signals, both ships had cut their engines, but their momentum carried them right on top of each other at slow speed.

Shortly before 9:00 am the Imo, headed out of Halifax Harbour and found itself on a collision course with the Mont-Blanc. After exchanging warning signals, both ships had cut their engines, but their momentum carried them right on top of each other at slow speed.

Unable to ground his ship for fear of a shock that would set off his explosive cargo, Mackey (an experienced harbour pilot) ordered Mont-Blanc to steer hard to port (starboard helm) and crossed the bow of Imo in a last-second bid to avoid a collision.

The two ships were almost parallel to each other, when Imo suddenly sent out three signal blasts, indicating the ship was reversing its engines.

The combination of the cargoless ship’s height in the water and the transverse thrust of her right-hand propeller caused the ship’s head to swing into Mont-Blanc. Imo’s prow pushed into the No. 1 hold of Mont Blanc, on her starboard side.

The collision occurred at 8:45 am. The damage to Mont Blanc was not severe, but barrels of deck cargo toppled and broke open. This flooded the deck with benzol that quickly flowed into the hold. As Imo’s engines kicked in, she disengaged, which created sparks inside Mont-Blanc’s hull. These ignited the vapours from the benzol.

The collision occurred at 8:45 am. The damage to Mont Blanc was not severe, but barrels of deck cargo toppled and broke open. This flooded the deck with benzol that quickly flowed into the hold. As Imo’s engines kicked in, she disengaged, which created sparks inside Mont-Blanc’s hull. These ignited the vapours from the benzol.

A fire started at the water line and travelled quickly up the side of the ship. Surrounded by thick black smoke, and fearing she would explode almost immediately, the captain ordered the crew to abandon ship.

A growing number of Halifax citizens gathered on the street or stood at the windows of their homes or businesses to watch the spectacular fire. The frantic crew of Mont-Blanc shouted from their two lifeboats to some of the other vessels that their ship was about to explode, but they could not be heard above the noise and confusion.

Just after 9:04 am, the Mont-Blanc exploded. The ship was completely blown apart and a powerful blast wave radiated away from the explosion initially at more than 1,000 metres (3,300 ft) per second.

Temperatures of 5,000 °C (9,000 °F) and pressures of thousands of atmospheres accompanied the moment of detonation at the centre of the explosion.

White-hot shards of iron fell down upon Halifax and Dartmouth. Mont-Blanc’s forward 90-mm gun landed approximately 5.6 kilometres (3.5 mi) north of the explosion site near Albro Lake in Dartmouth with its barrel melted away.

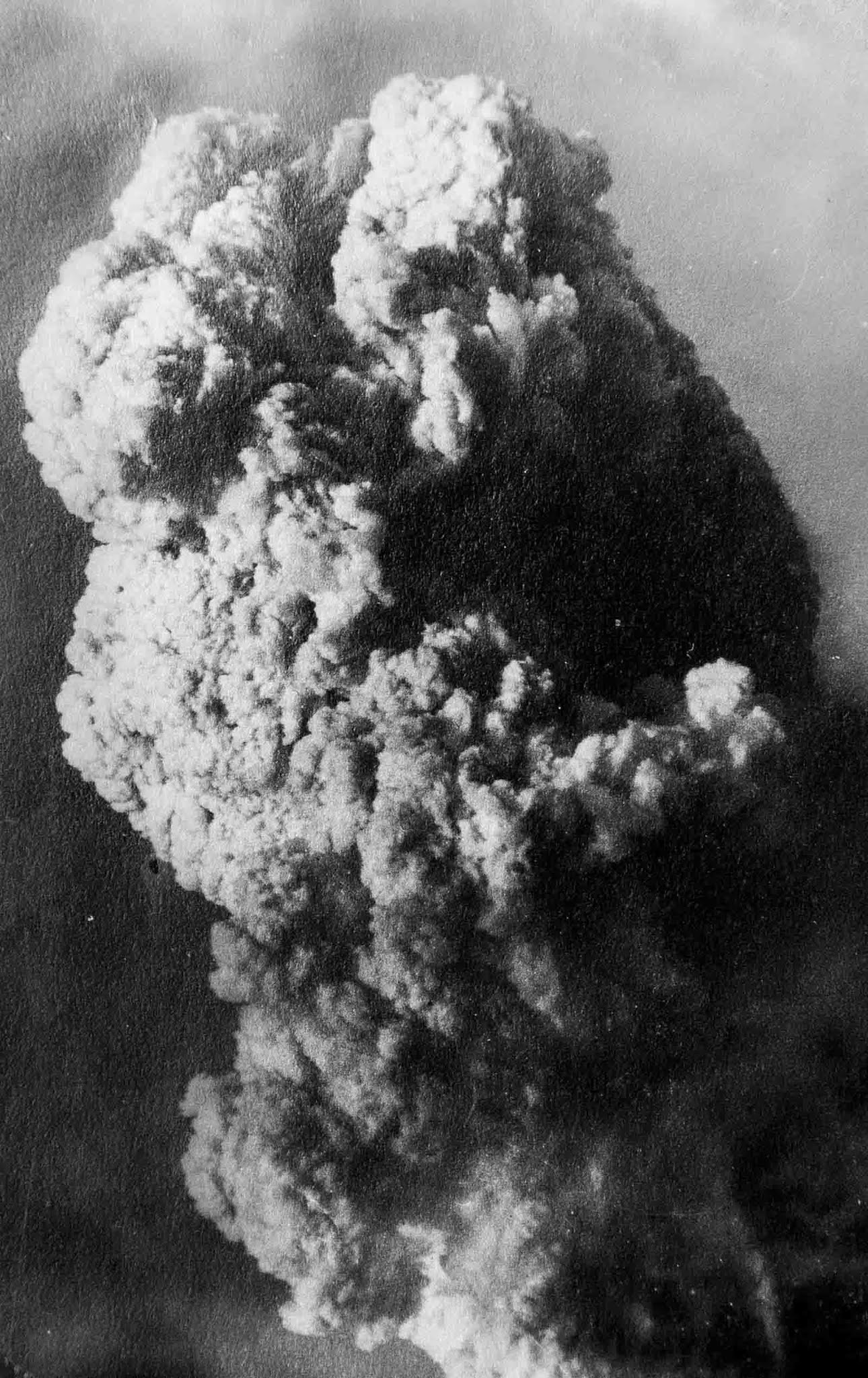

Smoke rises above Halifax minutes after the explosion.

A cloud of white smoke rose to at least 3,600 metres (11,800 ft).The blast was felt as far away as Cape Breton (207 kilometres or 129 miles) and Prince Edward Island (180 kilometres or 110 miles).

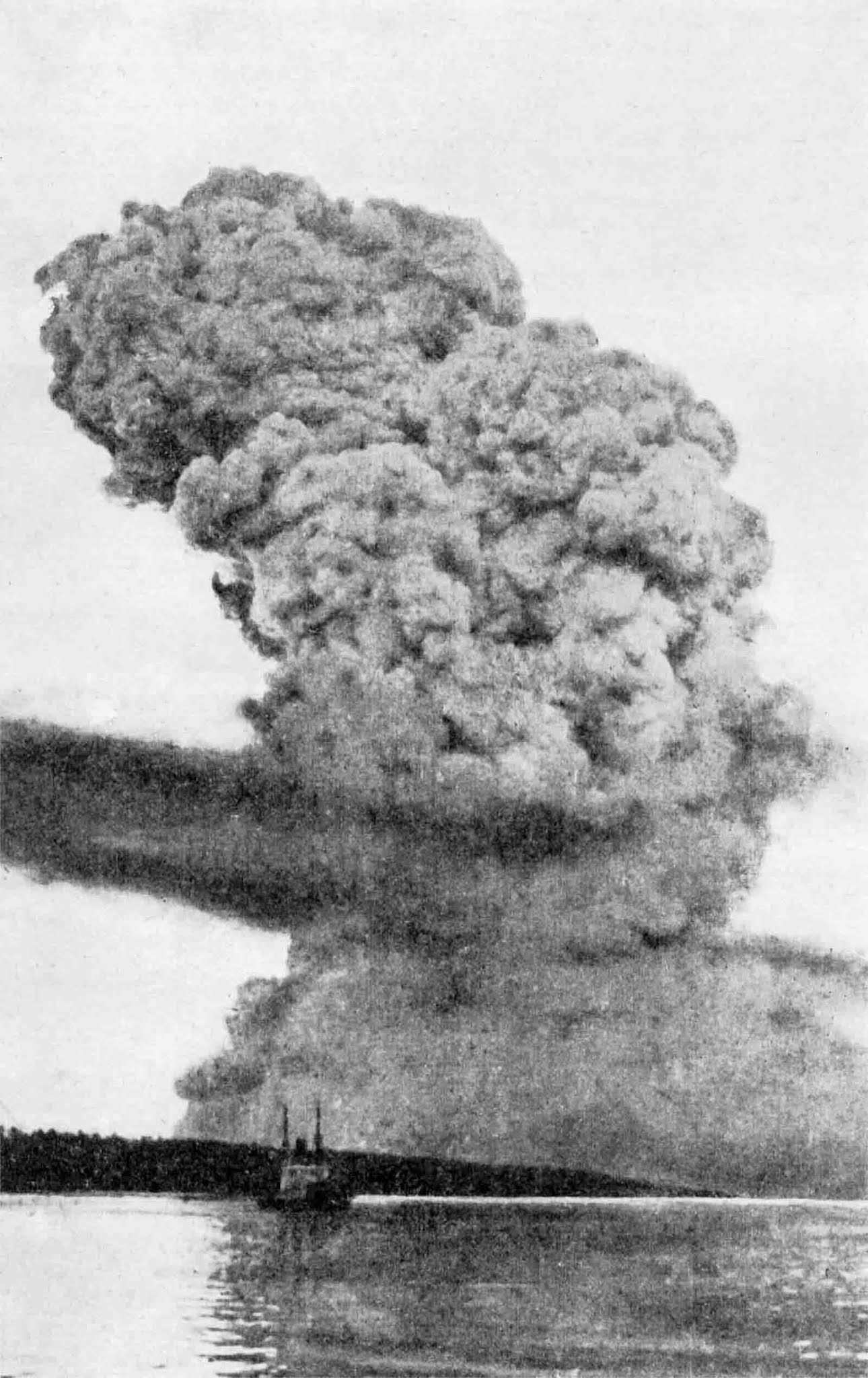

An area of over 160 hectares (400 acres) was completely destroyed by the explosion, and the harbour floor was momentarily exposed by the volume of water that was displaced. A tsunami was formed by water surging in to fill the void; it rose as high as 18 metres (60 ft) above the high-water mark on the Halifax side of the harbour.

Over 1,600 people were killed instantly and 9,000 were injured, more than 300 of whom later died. Every building within a 2.6-kilometre (1.6 mi) radius, over 12,000 in total, was destroyed or badly damaged.] Hundreds of people who had been watching the fire from their homes were blinded when the blast wave shattered the windows in front of them.

Overturned stoves and lamps started fires throughout Halifax, particularly in the North End, where entire city blocks burned, trapping residents inside their houses.

Firefighter Billy Wells, who was thrown away from the explosion and had his clothes torn from his body, described the devastation survivors faced: “The sight was awful, with people hanging out of windows dead. Some with their heads missing, and some thrown onto the overhead telegraph wires.” He was the only member of the eight-man crew of the fire engine Patricia to survive.

The Halifax Explosion was one of the largest artificial non-nuclear explosions, releasing the equivalent energy of roughly 2.9 kilotons of TNT (12 TJ).

An extensive comparison of 130 major explosions by Halifax historian Jay White in 1994 concluded that it “remains unchallenged in overall magnitude as long as five criteria are considered together: number of casualties, force of blast, radius of devastation, quantity of explosive material, and total value of property destroyed.”

The Norwegian ship SS Imo is run up against the Dartmouth shore by the tsunami generated by the explosion.

Halifax residents dig through rubble five days after the explosion.

Residents walk through a section of Halifax completely flattened by the blast.

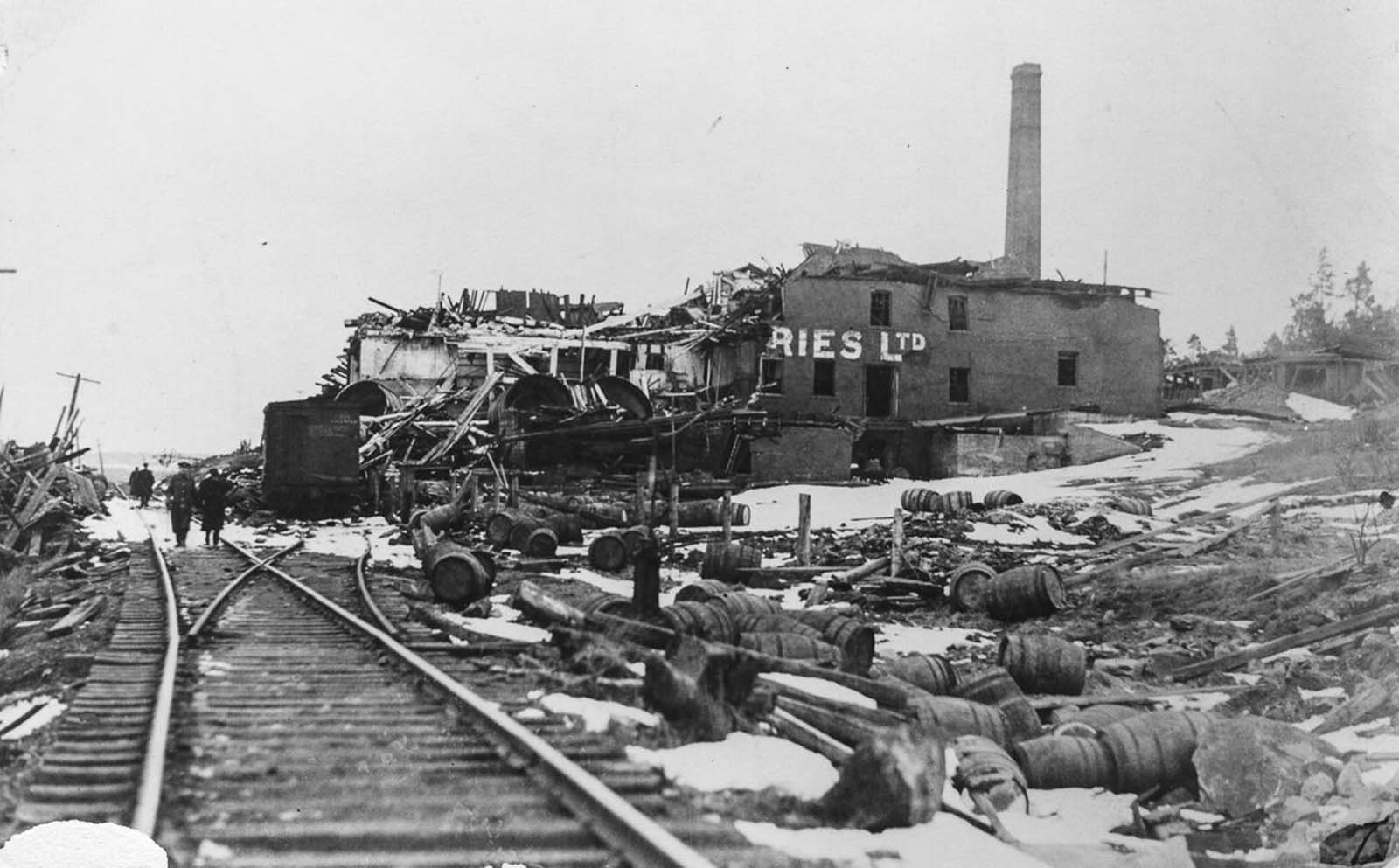

Railyards and ships lay devastated by the blast.

The Army & Navy Brewery in Dartmouth stands in ruin.

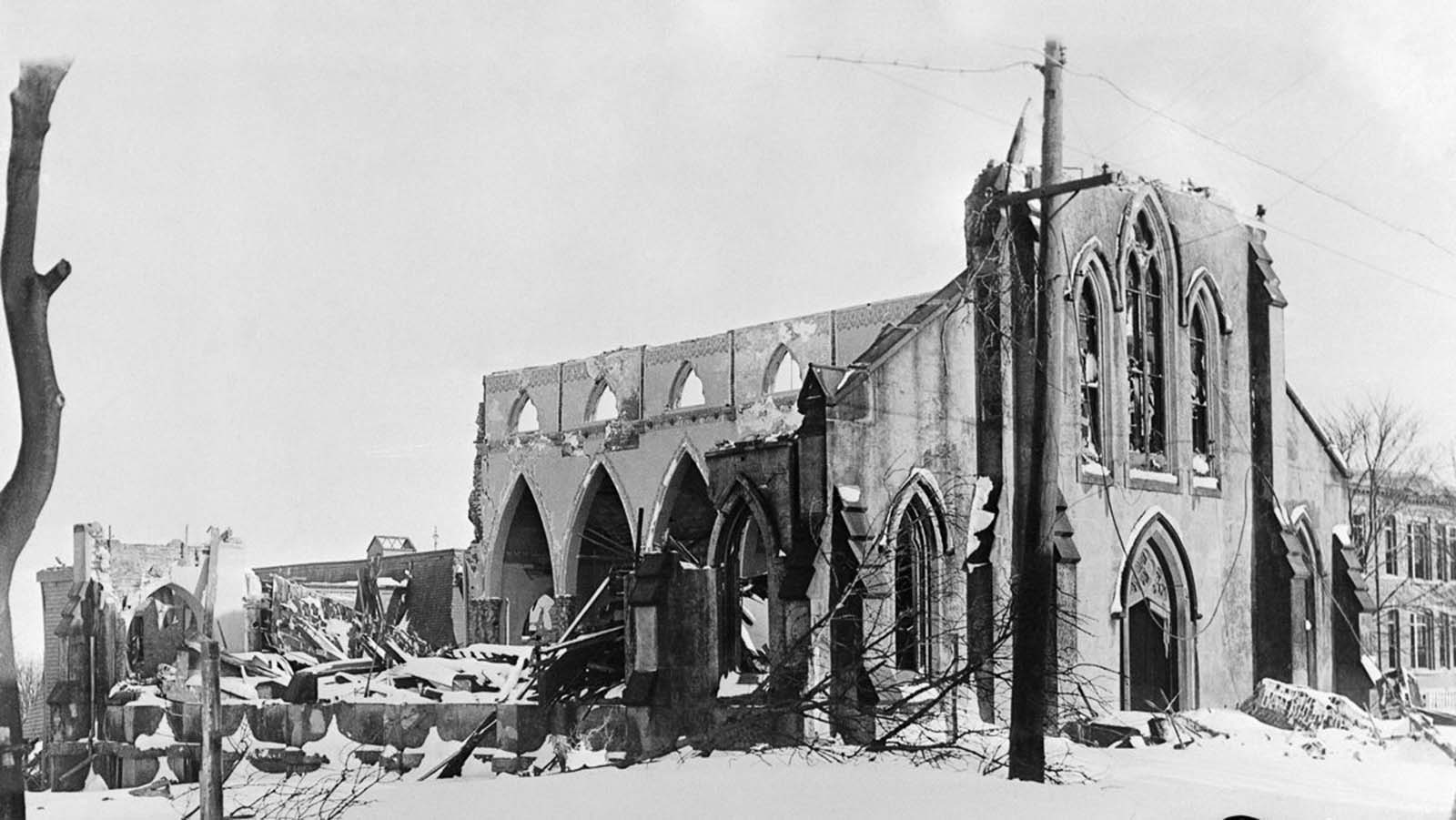

A cathedral stands in ruins.

American relief workers stand in front of the American relief hospital in Halifax.

Ruined houses on Campbell Road.

Tents are erected on the North Common of Halifax to house residents displaced by the disaster.

People pick through the ruins of the Nova Scotia Car Works in Halifax.

St. Joseph’s Convent stands with its roof collapsed and walls buckled.

Explosion aftermath: Halifax’s Exhibition Building. The final body from the explosion was found here in 1919.

Women walk into Halifax among the ruins on Campbell Road.

Soldiers stand guard amid ruined houses on Kaye Street in Halifax.

People wait for food and supplies at a relief station.

Children pick up food from a relief station.

A view looking north toward Pier 8 from Hillis foundry in Halifax.

Wrecked homes on Campbell Road.

A victim of the explosion is carried into a makeshift hospital at St. Mary’s College.

The SS Imo lists after being run aground by the force of the explosion.

Cleanup nears completion prior to the start of reconstruction, seven months after the disaster.

A view across the devastation of Halifax two days after the explosion, looking toward the Dartmouth side of the harbour. Imo is visible aground on the far side of the harbour.

Workers clear debris from the North Street Station.

The explosion devastated a large portion of Halifax (shown) and part of Dartmouth (off bottom of map).

(Photo credit: Nova Scotia Archives / Library and Archives Canada / Wikimedia Commons / The Halifax Explosion: Canada’s Worst Disaster).