Fascinating historical photos show families picking hops in the English countryside, 1900-1950

These fascinating black and white pictures show the hop picker families of Kent from the early 1900s. Before mechanization hop-picking was a hugely labor-intensive process. Consequently, farmers needed extra workers.

This help came in the form of families, usually women and children from London, who would arrive in Kent for three weeks in September to pick hops. Many saw it as a kind of holiday, a chance to exchange city life for the green fields of the countryside.

Hops are the flowers (also called seed cones or strobiles) of the hop plant Humulus lupulus, a member of the Cannabaceae family of flowering plants.

They are used primarily as a bittering, flavoring, and stability agent in beer, to which, in addition to bitterness, they impart floral, fruity, or citrus flavors and aromas.

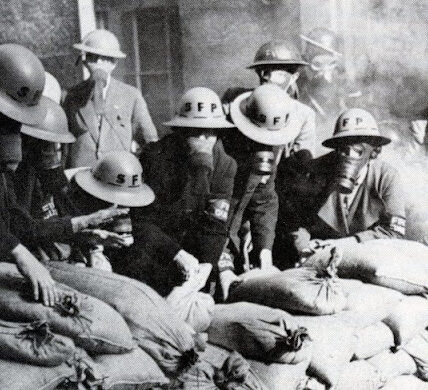

Hoppers at work at Whitbreads Farm at Beltring, Kent. 1930.

Hops are also used for various purposes in other beverages and herbal medicine. There are separate female and male hops plants, and only female plants are used for commercial production.

In Britain, hopped beer was first imported from Holland around 1400, yet hops were condemned as late as 1519 as a “wicked and pernicious weed”.

In 1471, Norwich, England, banned the use of the plant in the brewing of ale (“beer” was the name for fermented malt liquors bittered with hops; only in recent times are the words often used as synonyms).

Hops used in England were imported from France, Holland, and Germany and were subject to import duty; it was not until 1524 that hops were first grown in the southeast of England (Kent), when they were introduced as an agricultural crop by Dutch farmers. Consequently, many words used in the hop industry derive from the Dutch language.

Kent was the earliest center for hop culture as it had good soil, an enclosed field system, and a good supply of wood for poles and charcoal for drying that contributed to the creation of the first English hop garden near Canterbury in 1520.

Hop-picking as a job gained immense popularity in the Victorian era, and by the 1870s railway companies provided ‘Hop-Picker Specials’ to transport workers into Kent.

A family of hop pickers stand beside their packed cart. 1907.

Whole families would participate and live in hoppers’ huts, with even the smallest children helping in the fields. The final chapters of W. Somerset Maugham’s Of Human Bondage and a large part of George Orwell’s A Clergyman’s Daughter contain a vivid description of London families participating in this annual hops harvest.

In England, many of those picking hops in Kent were from eastern areas of London. This provided a break from urban conditions that was spent in the countryside. People also came from Birmingham and other Midlands cities to pick hops in the Malvern area of Worcestershire. Some photographs have been preserved.

The often-appalling living conditions endured by hop pickers during the harvest became a matter of scandal across Kent and other hop-growing counties.

Eventually, the Rev. John Young Stratton, Rector of Ditton, Kent, began to gather support for reform, resulting in 1866 in the formation of the Society for the Employment and Improved Lodging of Hop Pickers.

Particularly in Kent, because of a shortage of small-denomination coin of the realm, many growers issued their own currency to those doing the labor. In some cases, the coins issued were adorned with fanciful hops images, making them quite beautiful.

A family of hop pickers at Victoria Station in London. 1919.

In 1922 the first hop-picking machine to be used in this country was imported from America by a Worcester grower. Machine picking was not to become widely practiced until the late 1950s as the American machines were not suited to conditions in England and hand pickers were still available.

However, when the change came, it was the West Midlands growers who led the way. The first British-made picking machine was produced in Martley in 1934 and the two main makes were manufactured in Suckley and Malvern.

Eventually, in the 1950s, mechanized harvesting began replacing laborers on hop farms and the tradition declined. The Hopper Huts were demolished or turned into houses, though some were preserved in museums.

Hop pickers use stilts on a farm at Wateringbury in Kent. 1928.

Hop pickers arrive at the Kentish hop fields. 1910.

Hop pickers in a camp in the Kentish hop fields. 1910.

Hoppers tally off after picking. 1906.

Hop pickers at a camp in Faversham, Kent. 1932.

Hop pickers’ children watch as a Franciscan friar puts up a notice of a church service. 1933.

Salvation Army workers look after the children of hop pickers. 1936.

A woman prepares a meal for hop pickers at the Whitbread hop camp in Paddock Wood, Kent. 1937.

A group of young hop pickers enjoy glasses of milk from a milk bar near the fields in Kent. 1938.

A host serves lunch to a hop picking family in Kent. 1944.

Hop pickers move furniture into their summer quarters at Buston Manor near Maidstone, Kent. 1949.

A Franciscan friar and nun walk with hop pickers’ children at Paddock Wood, Kent. 1934.