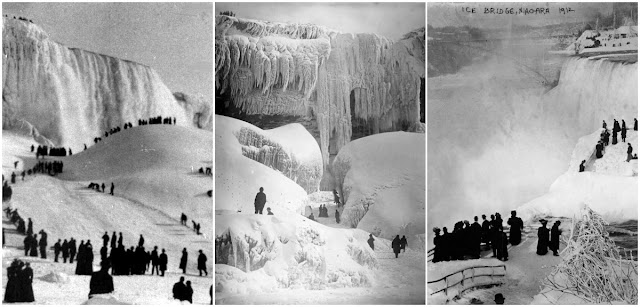

People used to walk to Canada across frozen-over Niagara Falls.

As temperatures drop in the northeast corner of the United States, icy water that goes over the roaring Niagara Falls crashes into the rocks below and turns solid. Blocks of ice floes freeze together, forming a solid mass wide enough to connect the United States and Canada.

It’s called the ice bridge. Children in the late 1880s rode their sleds there, tourists strolled between the two countries, and entrepreneurs sold food and hot drinks from makeshift concession stands. A “sharp rogue,” as the Niagara Falls Gazette described a man on Feb. 14, 1883, built a shanty of boards in the middle of the massive bridge – right on the line between the two countries, where no laws apply – and sold liquor.

Such was the geological wonder of the ice bridge and the three falls that form Niagara Falls in New York. American and Bridal Veil falls are next to each other on the U.S. side. Horseshoe Falls, the biggest of the three, straddles both countries. Collectively, more than 3,000 tons of water flows over the falls each second, making Niagara Falls a major source of hydroelectric power for the United States and Canada.

|

| 1850 |

|

| 1860s |

|

| 1880s |

|

| 1883 |

|

| 1883 |

|

| 1888 |

|

| 1890s |

|

| 1890 |

|

| 1894 |

|

| 1895 |

|

| 1900s |

|

| 1900s |

|

| 1900 |

|

| 1900 |

|

| 1902 |

|

| 1903 |

|

| 1911 |

|

| 1911 |

|

| 1911 |

|

| 1911 |

|

| 1911 |

|

| 1912 |

|

| 1916 |

|

| 1917 |