Britain’s path to 1.3MILLION immigrants in a single year: How the UK saw a century of net emigration – before Tony Blair ramped up numbers and a post-Brexit system sparked surge to record levels_Nhy

Politicians are wrestling with how to tackle an immigration crisis after shock figures showed numbers have hit a new record.

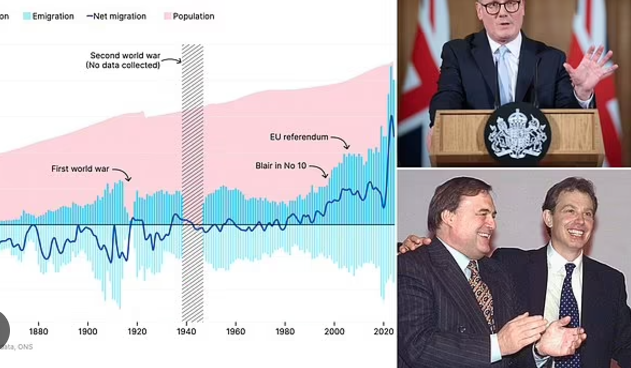

Long-term net migration was 906,000 in the year to June 2023 – the highest ever, driven by 1.3million arrivals.

The huge number emerged last night as the Office for National Statistics revised estimates for the past few years.

The difference between those coming to and leaving the UK was 728,000 in the most recent period, the 12 months to June this year. In itself that was almost as much as the previous long-term immigration peak.

However, the bar has been dramatically shifted upwards as net migration for the year to June 2023 is now thought to have been 166,000 above the initial estimate of 740,000.

A similar revision has been made for net migration in the year to December 2023, which was initially believed to be 685,000 and is now put at 866,000, an increase of 181,000.

The revelations sparked a bitter war of words between Labour and the Tories, with Keir Starmer accusing the previous government of being a ‘soft touch’ and pursuing an ‘open door’ policy after Brexit.

At a hastily-arranged press conference in No10, Keir Starmer accused the Tories of using Brexit to pursue an ‘open borders experiment’ saying they had failed ‘time and again’ to get the system under control

It was not until the late 1990s, when Tony Blair was elected, that immigration began to add significantly to numbers in the country.

The points-based system introduced under Boris Johnson was praised as fairer than EU free movement, but critics say it was too generous.

The PM vowed that he would bring legal immigration down ‘significantly’ – although he refused to give any specific level.

But figures compiled by the Bank of England and dating back to 1850 show that significant inflows to Britain are a very modern phenomenon.

Emigration dominated for well over a century, with UK population growth entirely due to there being more births than deaths.

In some years before the First World War the net outflow from the UK was more than 300,000 people.

It was not until the late 1990s, when Tony Blair was elected, that immigration began to add significantly to numbers in the country.

Among the key changes were loosening of work permit and international student rules.

The expansion of the EU then sparked a sharp rise in the mid-2000s, with large numbers coming from countries such as Poland and Hungary to work.

By the time of the Brexit referendum in 2016 official figures for net immigration were running at 323,000 a year – something that is thought to have contributed to the Leave result.

However, since then there has been another dramatic spike, only interrupted briefly by Covid travel lockdown.

The points-based system introduced under Boris Johnson was praised as fairer than EU free movement, but critics say it was too generous.

Many economists argue that workers need to come in from abroad to drive UK plc, but there have been calls for firms to attract more Brits into jobs.

A strong economy and labour market makes the country more appealing for would-be migrants.

The methodology for migration figures has changed over the years, and the Bank of England stresses that its historical dataset should be regarded as estimates based on ‘best endeavours’ rather than official statistics.

Under David Cameron and Theresa May there was a commitment to bring the long-term net migration figures into the tens of thousands.

The Conservative manifesto in 2019 pledged ‘numbers will come down’. At that point the level was around 240,000.

The Treasury’s OBR watchdog has forecast that net annual migration will subside to 315,000 a year over the ‘medium term’ – although that estimate now looks in serious doubt.

Its assessment published last month pointed to Home Office visa data covering the second quarter of 2024 showing a ‘sharp’ fall.

‘This largely reflects government restrictions coming into force in the first half of this year, which we now expect to have a slightly larger impact than we anticipated in March,’ the report released alongside the Budget said.

‘We judge the stronger outturn and larger policy impact to be broadly offsetting, and therefore project net migration will continue to fall in line with our March forecast.’

The OBR assessment published last month pointed to Home Office visa data covering the second quarter of 2024 showing a ‘sharp’ fall