If elections are about “the economy, stupid,” Ben McDuffee has not had the kind of confidence-boosting year that would make him feel good about keeping Democrats at the top of the ticket for four more years. And he is a Democrat.

The Lewisburg, Pennsylvania, resident lost his job late last year. He worked in financing for the auto industry and was unemployed for three months. During that time, he applied to more than 200 jobs. In March, he accepted a position at a local credit union — and a $30,000 pay cut.

That income hit, combined with higher prices at the grocery store and a recent increase in their monthly rent, meant tightening the budget. He and his wife put plans on hold to buy a home for themselves and their 11-year-old son, as interest rates rose, too.

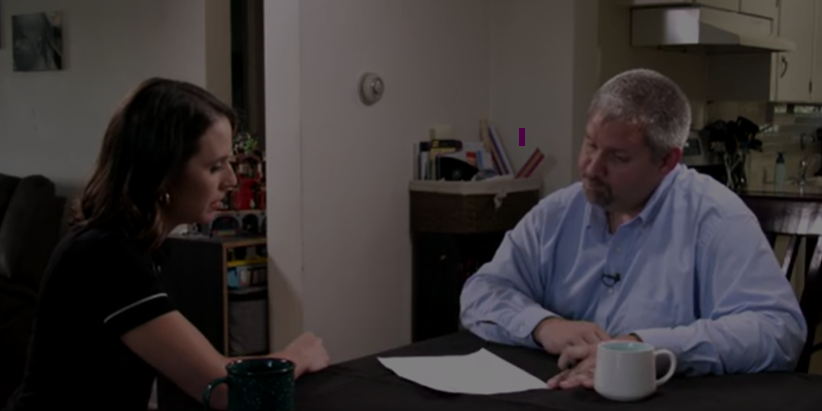

“You know, ultimately, the question that voters ask when they go to the polls every four years is, am I in a better spot than I was four years ago? And when we’re swiping our card for groceries every week, we are absolutely not in a better spot than we were four years ago,” McDuffee said in an interview with ABC News at his home.

“So, we have to balance that with — what do we think will happen with the country if we pick the other guy?”

From what he sees everyday in his rural Pennsylvania town — a sliver of one of the most critical swing states in the country — dislike of “the other guy,” former President Donald Trump, might not be enough for Vice President Kamala Harris to overcome what he sees as a major liability: the economy.

It’s the reality of this election, and it rings especially true in his battleground state: despite a strong recovery from the global pandemic — including record-low unemployment, increased wage growth and consistently sturdy consumer spending — the economy is still a top concern for voters.

According to an ABC News-Washington Post/Ipsos poll, more than 85% of adults rank the economy and inflation as highly important for their vote for president, by far the two highest-ranking issues. And voters trusted Trump over Harris on both issues by 9 points.

“There’s a disconnect between these macroeconomic numbers that are coming out and then what we’re hearing people are reporting about how they feel about the economy,” Heidi Shierholz, the president of the Economic Policy Institute and a former chief economist for the Department of Labor during the Obama administration.

A major reason it’s such a steep political challenge, she says, is that high prices are more obvious to people on a daily basis than national statistics or even their own pay raise.

“People’s living standards are actually growing despite the higher price level. So what’s going on now is actually what we want to see,” Shierholz said. “But it still is frustrating when you go to the grocery store or wherever and you see these high prices. You don’t always think in the back of your head, ‘Well, I also got that big wage increase, I can cover this and still be okay’.”

Since the peak of the pandemic recession, the U.S. has seen an increase in overall consumer prices by 20%, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, while the inflation-adjusted wages have also risen, on average, by about 25%.

That leaves some people feeling worse off than they actually are — and for people like McDuffee, who have seen their income fall or stay flat, the squeeze of higher prices is particularly sharp.

“I don’t doubt the numbers. But it all comes down to what you can do with the money that you have for your family. And you don’t feel all of all these great numbers,” McDuffee said.

It’s a perception Harris knows she will need to reverse to win over voters in critical battleground states like Pennsylvania, which could be key to winning her the presidency.

“Today, by virtually every measure, our economy is the strongest in the world,” Harris said in a recent campaign rally focused on the economy in North Carolina. But she was also careful to try not to alienate voters who don’t feel those impacts.

“We know that many Americans don’t yet feel that progress in their daily lives. Costs are still too high. And on a deeper level, for too many people, no matter how much they work, it feels so hard to just be able to get ahead,” Harris added.

To address this concern, Harris and President Joe Biden have pushed a “lowering costs” campaign, a handful of policies aimed at bringing down daily prices for people.

Efforts like negotiating down the price of drugs covered by Medicare, so seniors pay less for their prescriptions, and passing regulations that require companies to disclose “junk fees” on products like hotel rooms or concert tickets. For nearly 4.8 million people, the administration has canceled student loans.

For McDuffee, these policies aren’t cutting through.

He will reluctantly vote for Harris, he says, but he knows that many voters will prioritize their bank accounts in November.

“The only thing that I think a lot of consumers feel is when they swipe their card at the gas pump, at the grocery store, you know, buying back-to-school clothes, all of those items are more expensive than they were four years ago,” McDuffee said. “And I think that’s what resonates.”

Three hours southeast, though, Philadelphia City Councilmember Katherine Gilmore Richardson says she’s an example of why the Biden administration’s piecemeal policies are working — and have exponentially changed her family’s economic trajectory.

“No hesitation at all. I’m better off than I was four years ago. My family is better off because of the work of the Biden-Harris administration. And my children will be better off because of the Biden-Harris administration, if nothing more,” she said in an interview at her home in West Philadelphia.

Richardson, who has worked for the city for over 20 years, had her student debt canceled as part of major reforms to the Public Service Loan Forgiveness program, or PSLF, which allows peoples’ remaining debts to be forgiven after they’ve worked in public service and made loan payments for 10 years.

She has since helped her husband and her sister, who both work in non-profits and social work, respectively, to have their debts canceled, as well.

Through her family’s savings on student debt payments, Richardson, a mother of three, enrolled her two youngest children in one-on-one reading camp this summer.

Yet Richardson knows that receiving debt relief is a unique reason to feel good about the economy. Of the 43 million Americans with student loan debt, roughly one in 10 have so far had loans canceled by the Biden-Harris administration.

“I do hear from my constituents who have a number of concerns regarding the economy and their ability to be able to afford good quality housing to, you know, for food costs and to be able to take care of their families,” Richardson acknowledged.

Still, a delegate to the Democratic National Convention and a big fan of both Biden and Harris, Richardson says she believes her story reflects ongoing efforts to reduce financial burdens and a reason to re-elect the Democrats.

“I think we have to do a better job of telling that story and talking about the work that they’re seeking to do,” she said.