The Labour Party Conference took place this week, with the usual platitudes and feel-good anecdotes to inspire the party’s natural supporters. And who can blame them?

After a week of “freebie” scandals and a leak investigation into bad briefings, any good press for Labour right now is like finding an oasis in the desert.

Despite the constant talk of “joy”, “optimism” and “hope”, members of the British public are still wondering just how joyful, optimistic or hopeful Labour thinks most pensioners are feeling right now. Especially with the prospect of freezing to death this winter.

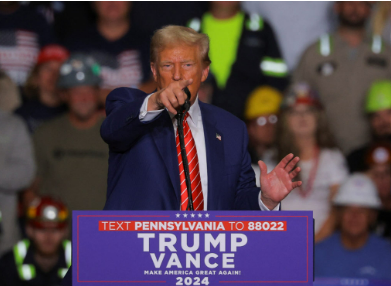

Keir Starmer acknowledged concerns about immigration were ‘legitimate’. (Image: Getty)

And what little talk there was of policy at the conference lacked any real substance. Even after a few days, I still cannot tell you what Labour plans to do for the country other than eventually “turn the corner”. OK? But, for most people, the priority was to see what Labour had to say about the country’s number one issue: immigration. And on that point, the Prime Minister deserves some credit.

He not only mentioned it (a very low bar indeed), but he also acknowledged concerns about immigration were “legitimate”. He committed his Government to not only reduce net migration but also lessen our economic dependency on it – and even went as far as to say that “there are plenty of examples of apprenticeships going down at the very same time that visa applications for the same skills are going up. And so, we will get tough on this”.

The key question, of course, is how? And what exactly does “getting tough” look like?

Sir Keir’s comments on immigration were predictable, vague and balanced – with just enough coverage to give the impression he’s not completely tone-deaf on the issue. For this, Labour HQ must be glad. However, his later comments, and those of his Home Secretary Yvette Cooper, highlighted just how far behind Labour truly is on this issue. In what turned out to be the most enthusiastically received part of his speech, the PM rejected “those who say that the only way to love your country is to hate your neighbour because they look different” – a very fair point.

Of course, we must reject violence and hatred. But who exactly is making the opposite case? Why allow the actions of a few thugs and racists to frame an essential debate about social integration, British values and national identity?

Would Sir Keir feel differently if people rejected their neighbours because they “acted” differently? Or, worse still, does he think the country would have jumped for joy if the person alleged to have murdered three little girls at a dance class in Southport happened to be white? Of course not. There are deep social divisions in this country that transcend the violence we saw in Southport. And Labour knows this.

Incredibly, while discussing the mass migration, Ms Cooper managed to miss the elephant in the room. How does she plan to make good on any of her promises without drastically cutting immigration numbers (both legal and illegal)? How on earth can Labour talk about house building, cheaper energy, encouraging domestic jobs, investing in our schools, reforming the NHS, and all the other things that the public is genuinely concerned about without first addressing immigration?

The latest figures put net migration into Britain for the last two years at 1.2 million people. That is 1.2 million more people using our roads, national health service, schools, water, and energy. Plus, more than 25,000 people have crossed the Channel in small boats so far this year (so much for “smashing the gangs”).

How will the Government raise the money needed to accommodate hundreds of thousands of new immigrants every year, given the myriad of problems this country faces?

It is clear that for much of the Labour Party, immigration is not a top concern – even though it affects virtually all aspects of public life. That is how far the cognitive dissonance goes.

Unsurprisingly, Ms Cooper parroted the same line as the PM, arguing that “many people have legitimate concerns about immigration”. Except, she didn’t actually address them.

What exactly are those “legitimate” concerns as you understand them, Ms Cooper? And how are people expected to express those concerns without being maligned as callous racists? Immigration is clearly the bogeyman for Labour. But it’s not going away anytime soon.

Ms Cooper can call people “right-wing wreckers” as much as she wants. But the truth is nothing will change until we see immigration figures, both legal and illegal, fall substantially.

SEE MORE :

Reeves urged to cut ‘extremely valuable’ public sector pensions

Rachel Reeves should cut public sector workers’ “extremely valuable” pensions at her maiden Budget, a leading think tank has said, amid continued pressure from unions over pay rises.

The Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) told the Chancellor that there is a “good case” for lowering pensions for public sector workers to fund future pay rises after the Government granted inflation-busting settlements to doctors, teachers and nurses.

Rachel Reeves granted inflation-busting pay settlements to doctors, teachers and nurses in July Oli Scarff/AFP via Getty Images

The report published ahead of the Budget on Oct 30 warns that to overcome recruitment difficulties the Treasury must reform rather than just raise pay amid a surging wage bill.

It also noted the disparity between public sector and private sector pensions: “Public sector pensions remain extremely valuable relative to private sector comparators. The pension contributions from public sector employers are higher than those often seen for even high-earning private sector employees.”

The report comes weeks after the Treasury signed off £9bn in pay increases for millions of public sector workers, close to half the size of the £22bn “black hole” in the public finances which Ms Reeves claims was left by the Conservatives.

Sir Keir Starmer has pledged to “rebuild” Britain’s public services and “protect working people”.

But the IFS warned recruitment and retention issues loomed large across the public sector, highlighting prison officers, district judges and secondary school teachers as roles with the biggest challenges.

Unions have meanwhile signalled that this year’s pay settlements do not mean their job is done.

After accepting a 22pc pay rise for junior doctors, the British Medical Association warned Wes Streeting, the Health Secretary, that there was “a long way to go” adding that “he needs to be prepared for the consequences” if future deals disappoint.

Closing the gap that has emerged between public and private sector pay rises since 2019 alone could result in a pay bill £17bn higher than today, according to the IFS.

Even uprating pay for public sector staff in line with earnings growth forecasts could land the Treasury with an annual bill of £6bn more.

Given such costs, the IFS said the Treasury should consider overhauling the entire pay system, targeting gold-plated pensions.

Andrew McKendrick, an author of the report, said: “Government needs to structure remuneration to make sure it is getting the right people in the right roles to help deliver public services. That might mean carefully rebalancing away from pensions and also towards higher-paid professions.”

Workers in the NHS receive an employer pension contribution of 23.7pc, police staff 35.3pc and those in the Armed Forces 43.8pc.

In contrast, an automatically enrolled worker in the private sector must contribute 8pc of their earnings that fall within £6,240 and £50,270.

Of the 8pc, only 3 percentage points must come from the employer.

This means an average earner on £35,000 would receive contributions equivalent to only 2.5pc of their total pay.

Higher minimum thresholds for employee contributions in the public sector than in the private also leave lower-paid staff struggling, the IFS warned.

Mr McKendrick said: “Public sector pensions remain far more valuable than those in the private sector, but significant numbers of lower-paid staff miss out as they cannot afford to make the required employee contributions.”

One in seven public sector workers earning between £10,000 and £16,000 a year are opting out of their pension scheme. This is more than twice the rate among those earning at least £31,000.

Higher-paid public sector workers and those based in London and the South East have seen the largest real-terms pay cuts, the IFS said.

This contributes to the difficulty of hiring for the highest paid public sector roles, according to the think tank.

Mr McKendrick said: “There continue to be big geographical differences in how well public sector pay compares with private sector pay. Gaps in pay between the two sectors are often bigger, and recruitment problems worse, for higher-paid groups such as judges and senior civil servants.”