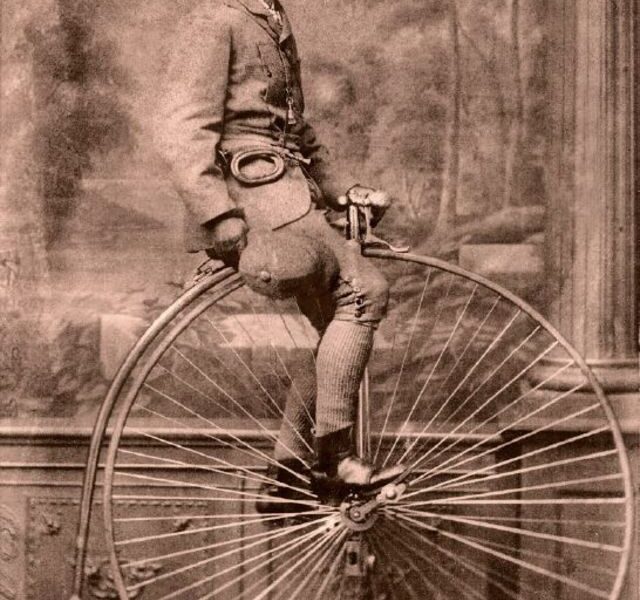

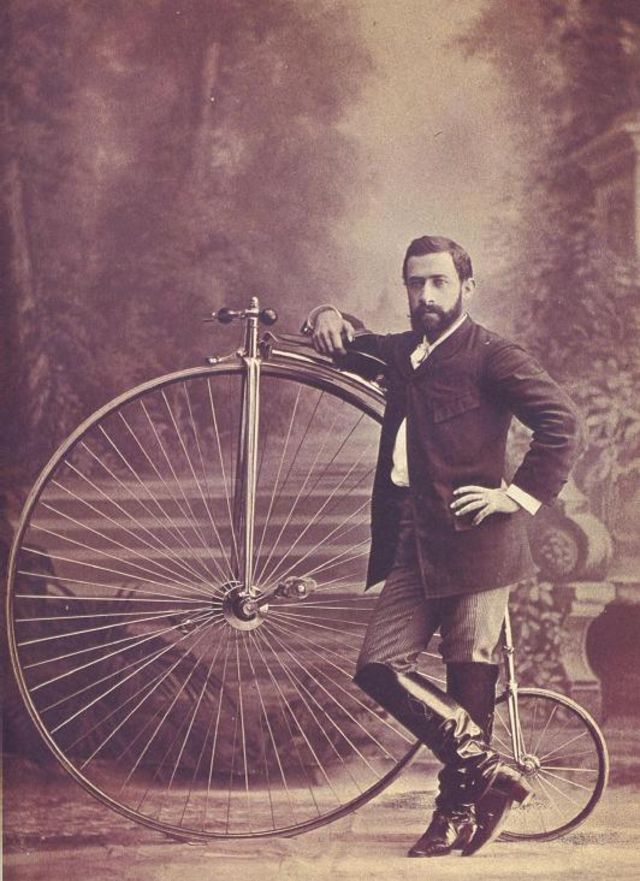

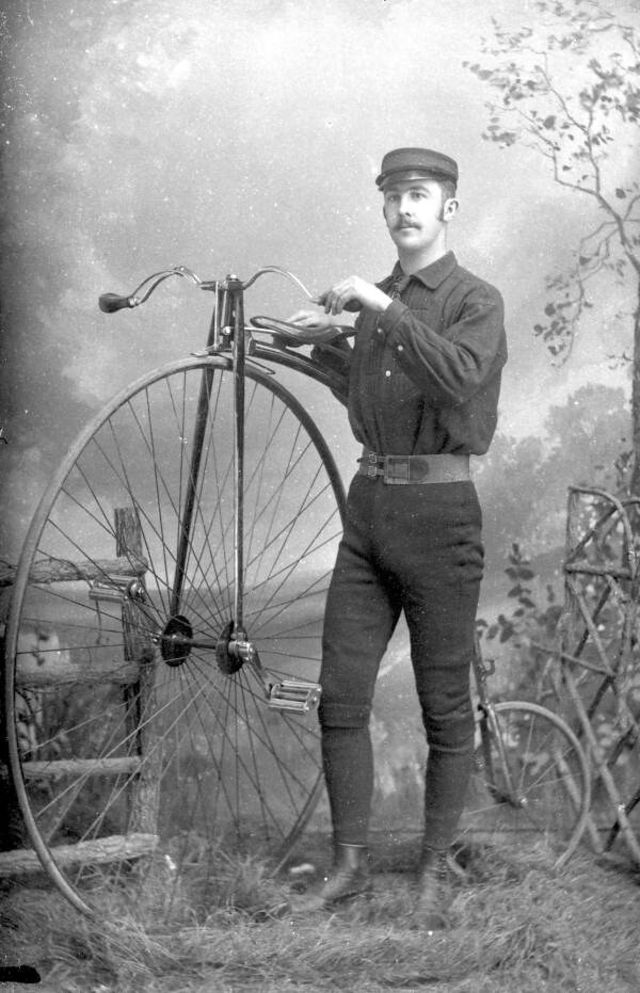

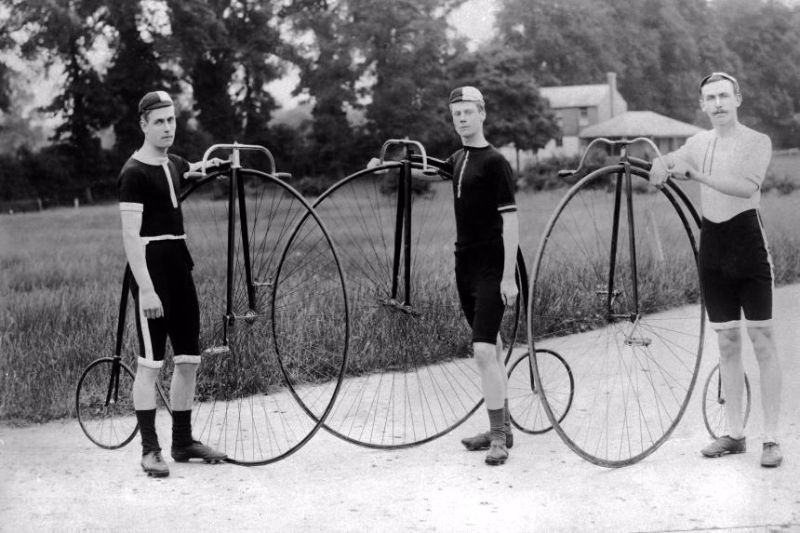

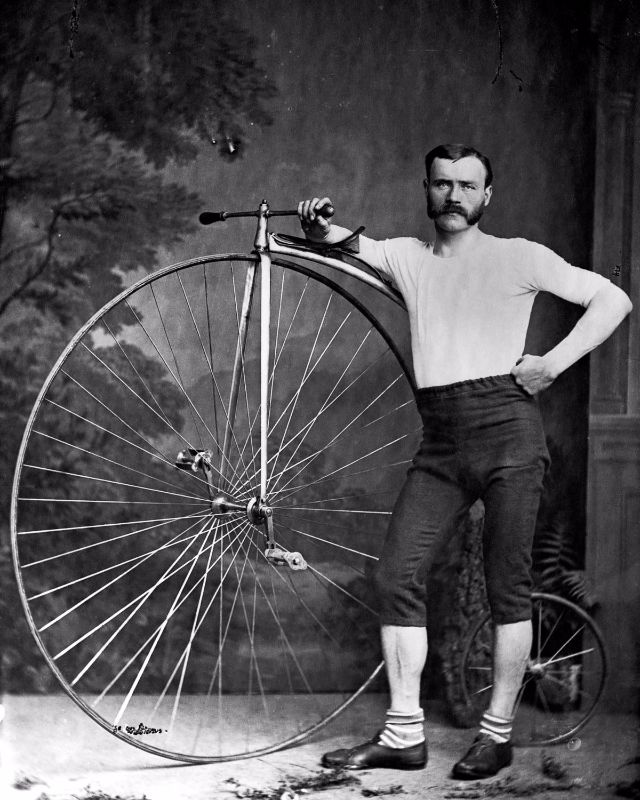

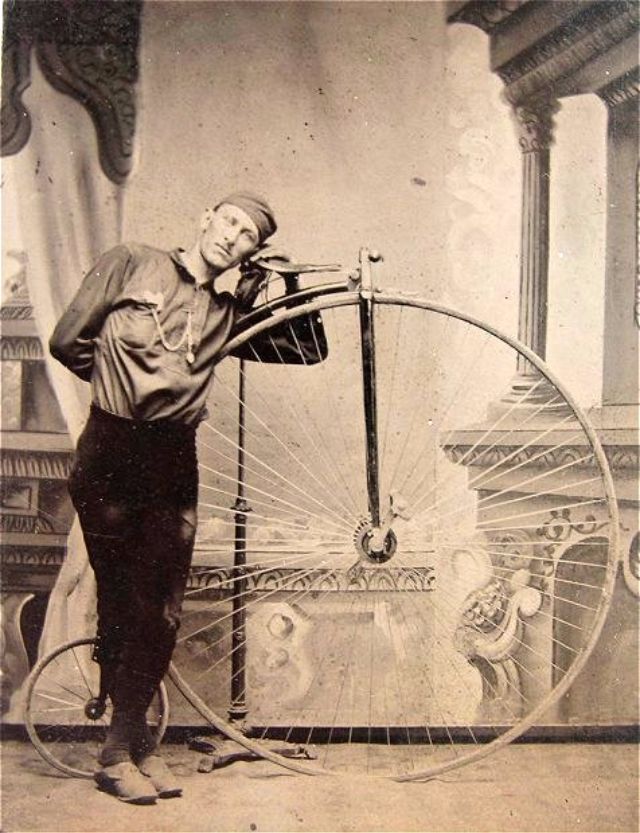

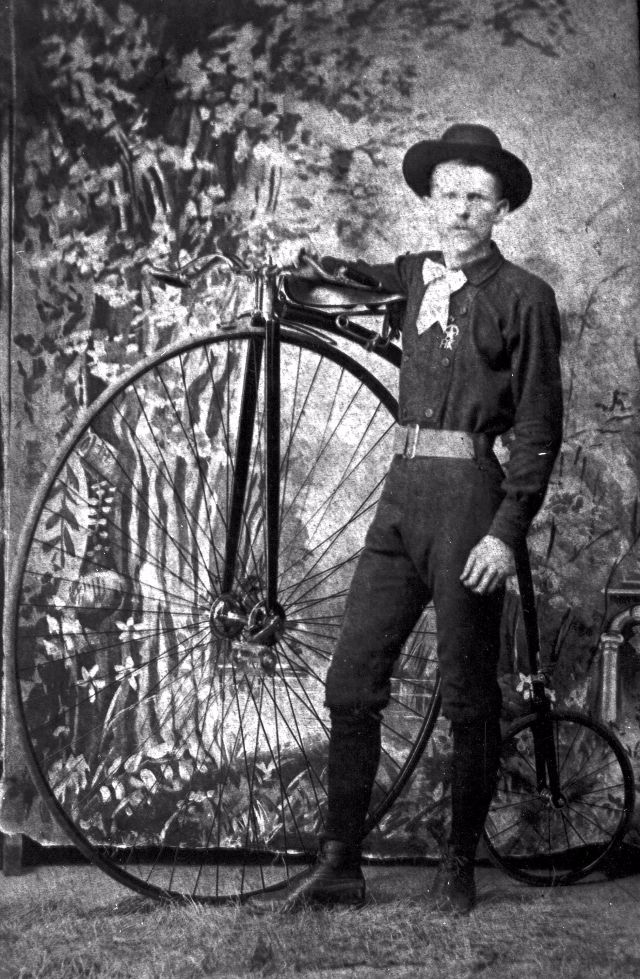

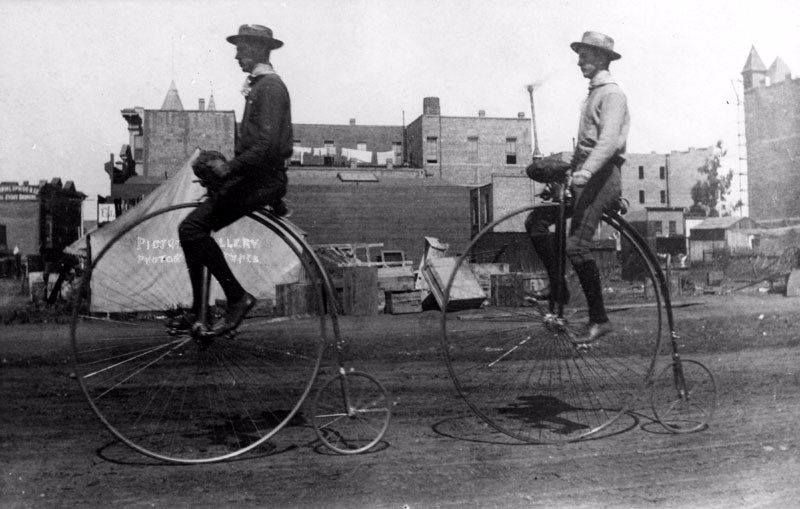

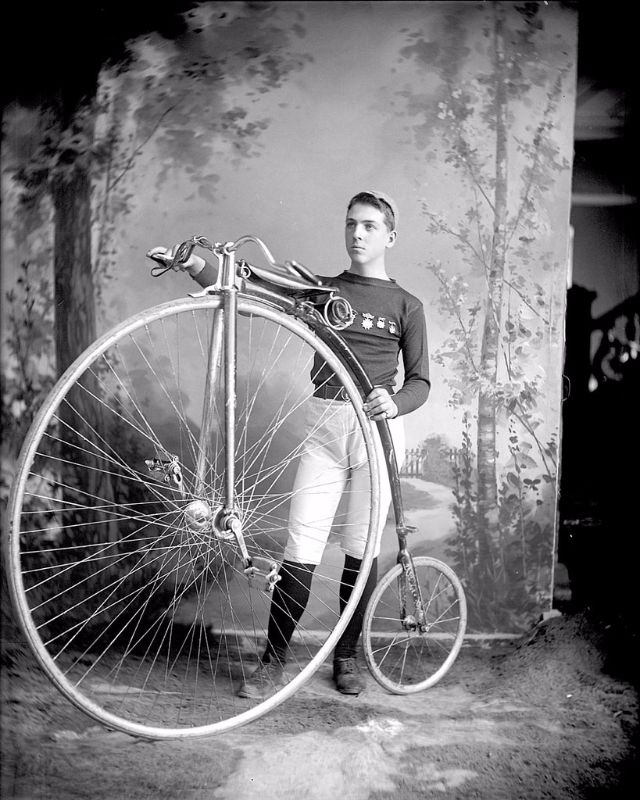

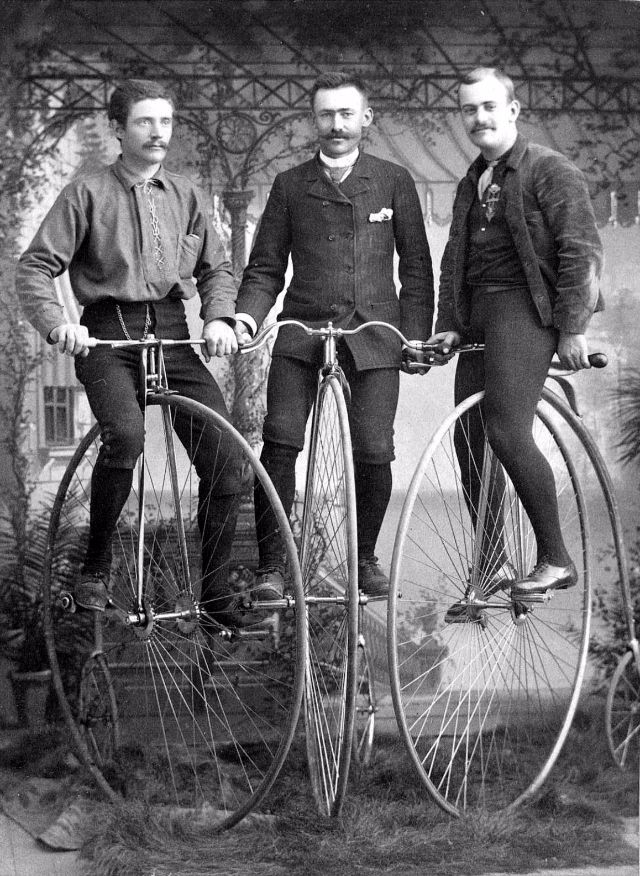

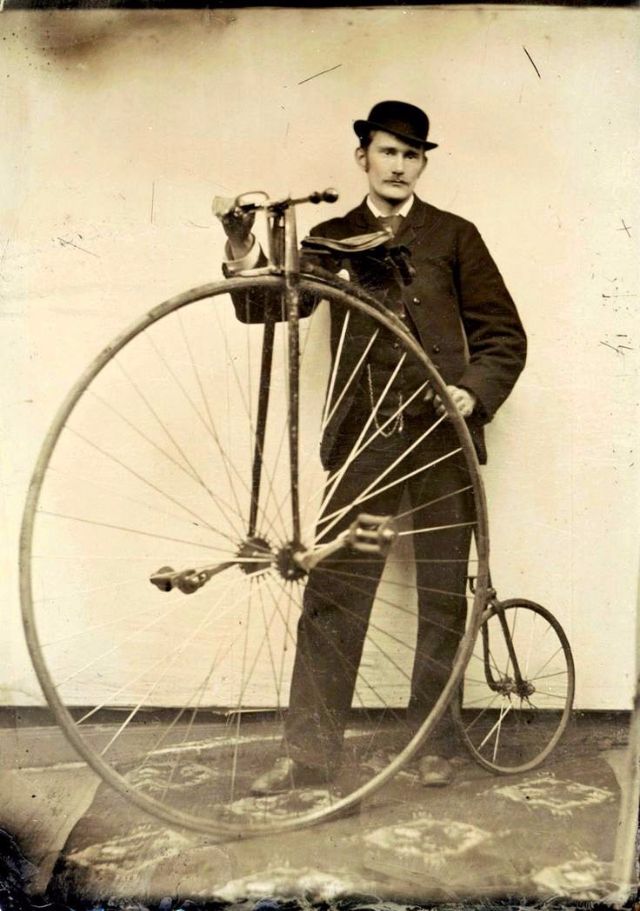

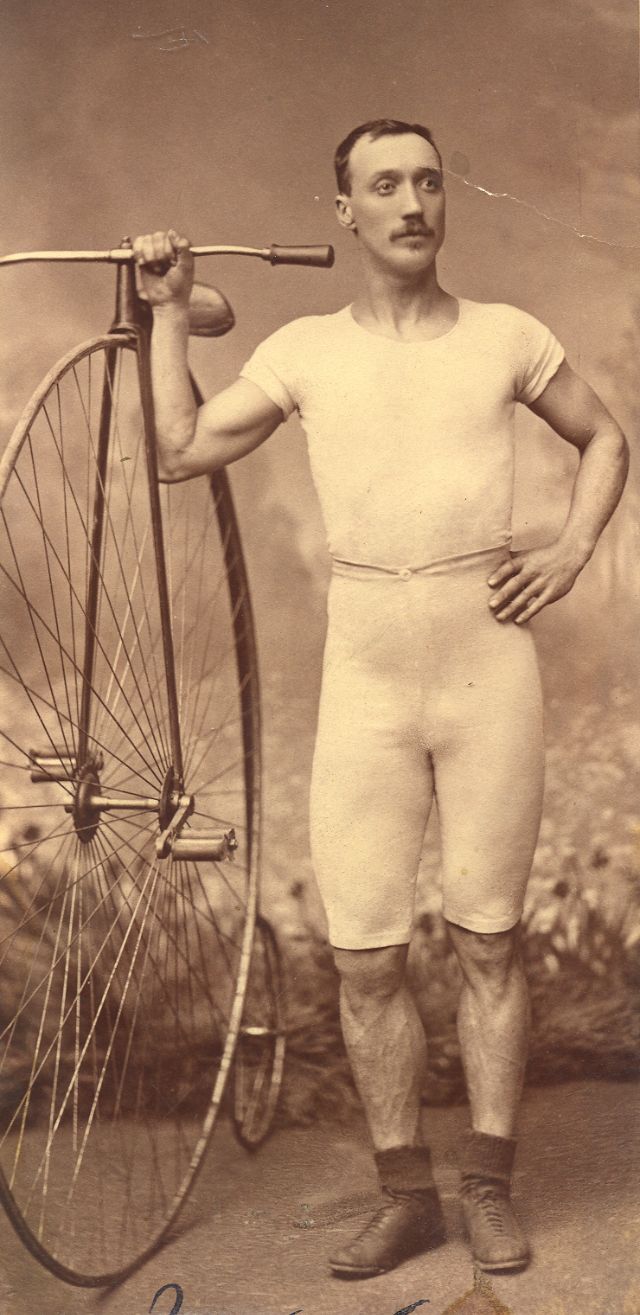

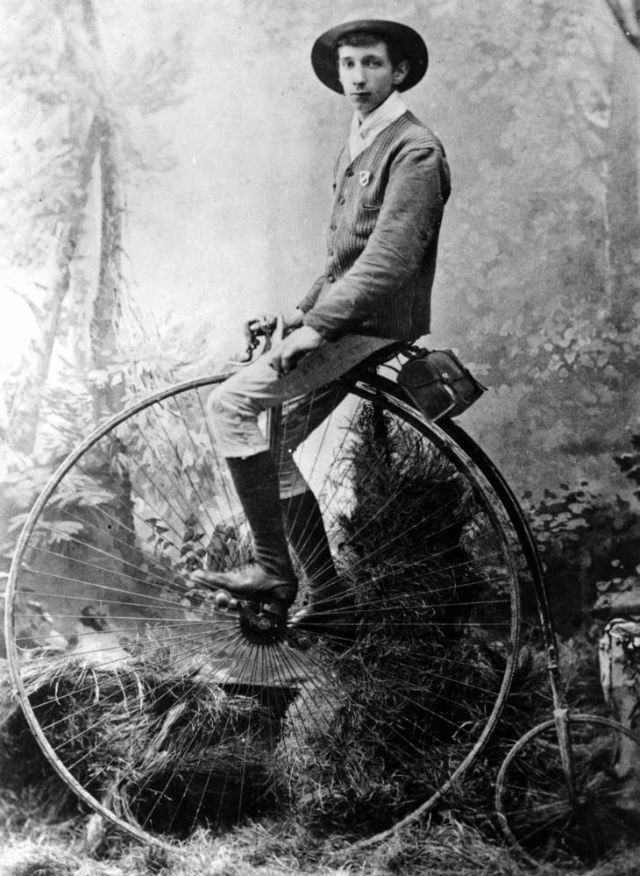

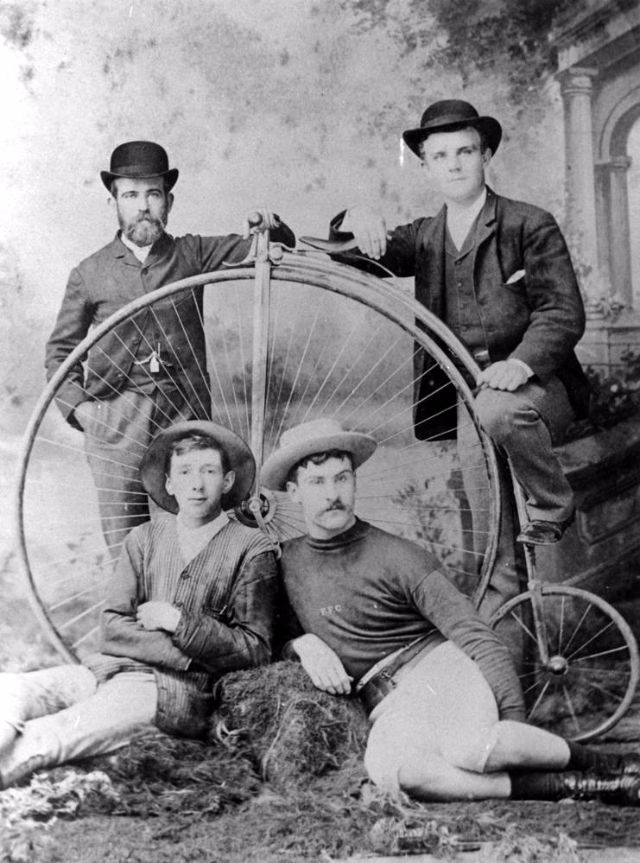

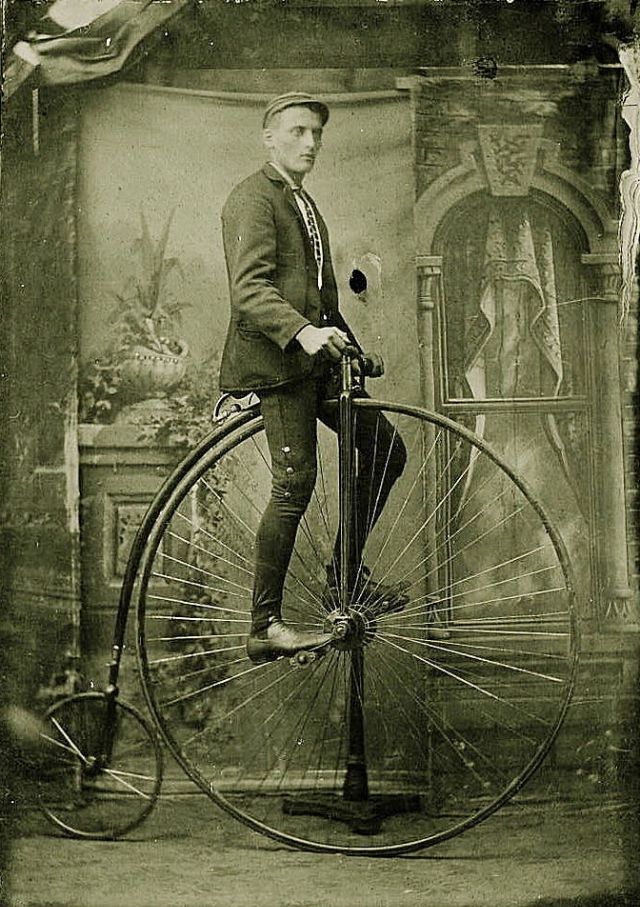

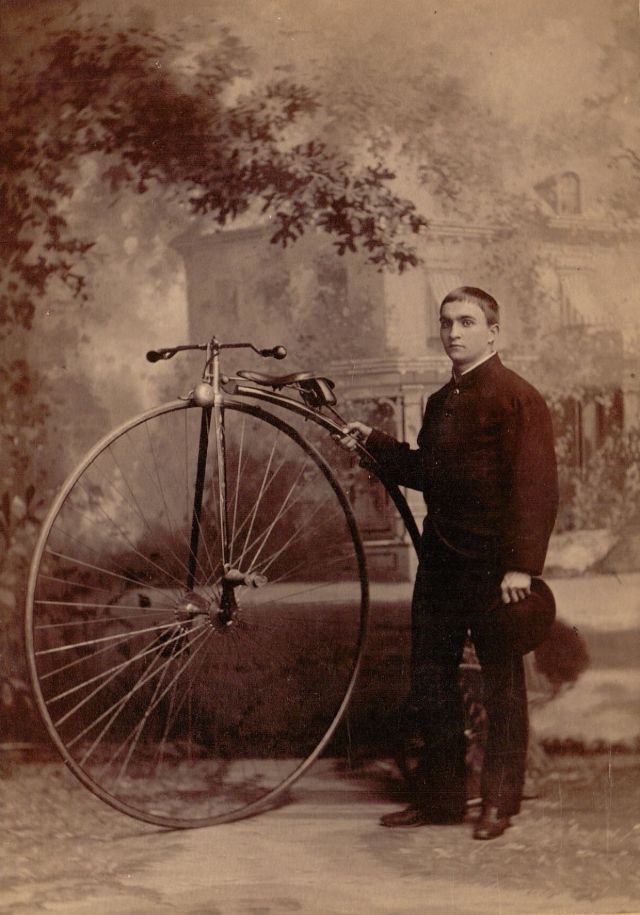

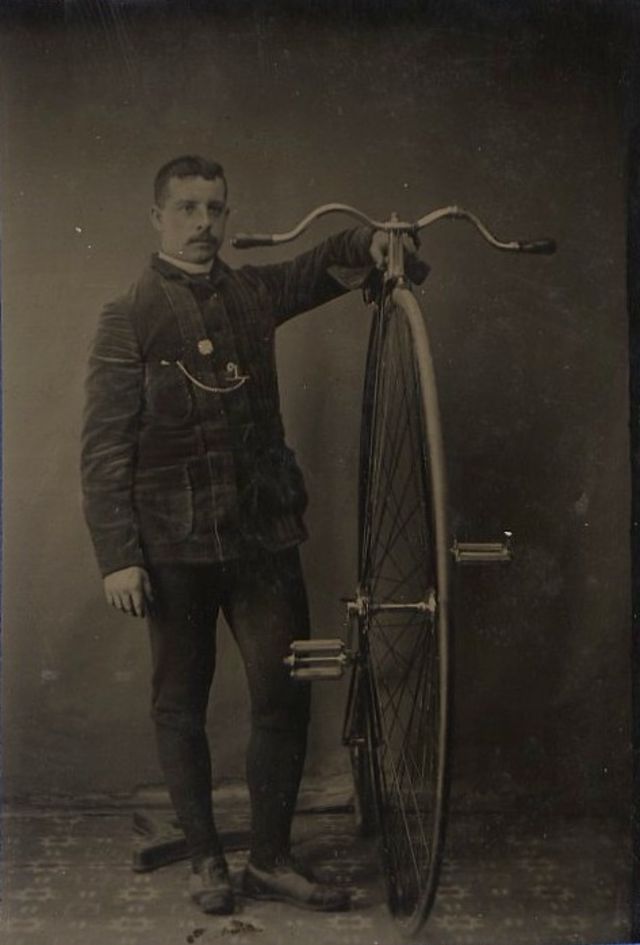

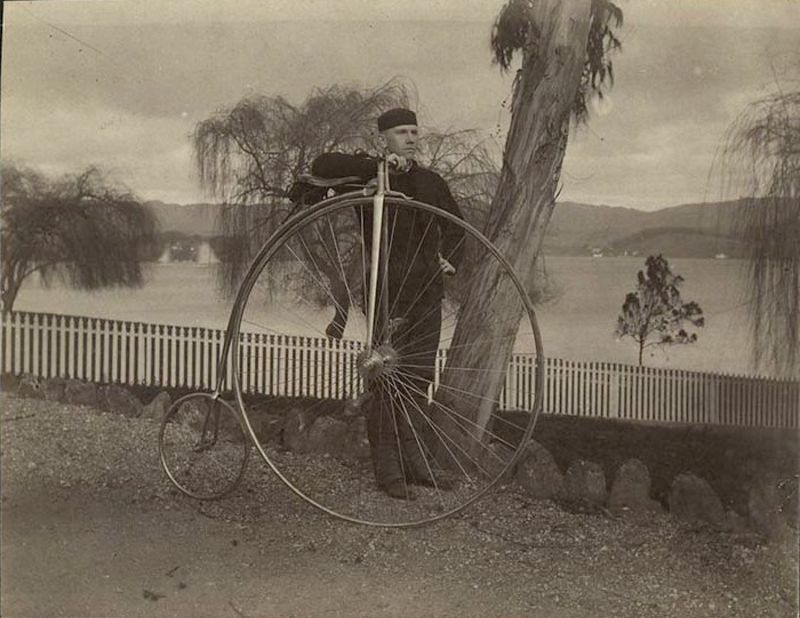

In the history of the bicycle, the penny-farthing stands tall—or rather, stands tall and rides even taller.

With its distinctive design, characterized by a comically large front wheel and a diminutive rear wheel, the penny-farthing catapults us back to the bygone era of the 19th century.

But what compelled riders to perch atop these towering contraptions, navigating the cobbled streets with an air of audacious elegance?

The penny-farthing, affectionately named for the British penny and farthing coins that bore a similar size resemblance, made its grand entrance onto the cycling stage in the 1870s.

Although the name “penny-farthing” is now the most common, it was probably not used until the machines had been almost superseded.

Although the name “penny-farthing” is now the most common, it was probably not used until the machines had been almost superseded.

The first recorded print reference is from 1891 in Bicycling News. For most of their reign, they were simply known as “bicycles”, and were the first machines to be so called, although they were not the first two-wheeled, pedaled vehicles.

Eugène Meyer of Paris is now regarded as the father of the high bicycle by the International Cycling History Conference in place of James Starley.

Meyer patented a wire-spoke tension wheel with individually adjustable spokes in 1869. They were called “spider” wheels in Britain when introduced there. Meyer produced a classic high bicycle design during the 1880s.

James Starley in Coventry added the tangent spokes and the mounting step to his famous bicycle named “Ariel”. He is regarded as the father of the British cycling industry.

Ball bearings, solid rubber tires and hollow-section steel frames became standard, reducing weight and making the ride much smoother.

Penny-farthing bicycles are dangerous because of the risk of headers (taking a fall over the handlebars head-first).

Makers developed “mustache” handlebars, allowing the rider’s knees to clear them, “Whatton” handlebars that wrapped around behind the legs, and ultimately (though too late, after the development of the safety bicycle), the American “Eagle” and “Star” bicycles, whose large and small wheels were reversed.

This prevented headers but left the danger of being thrown backward when riding uphill.

The penny-farthing used a larger wheel than the velocipede, thus giving higher speeds on all but the steepest hills.

The penny-farthing used a larger wheel than the velocipede, thus giving higher speeds on all but the steepest hills.

In addition, the large wheel gave a smoother ride, important before the invention of pneumatic tires.

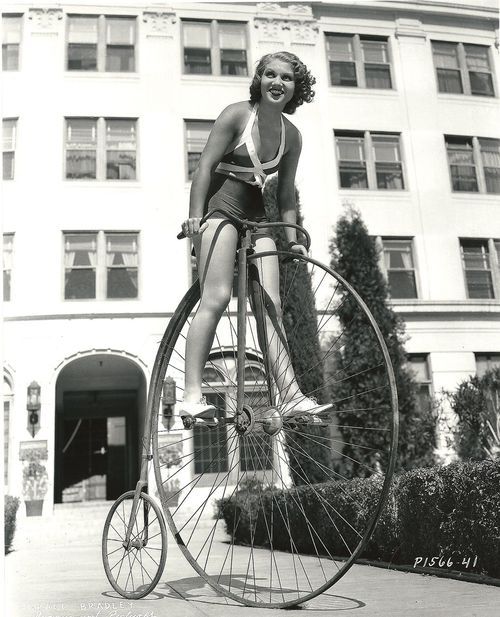

Although the high riding position seems daunting to some, mounting can be learned on a lower velocipede.

Once the technique is mastered, a high wheeler can be mounted and dismounted easily on flat ground and some hills.

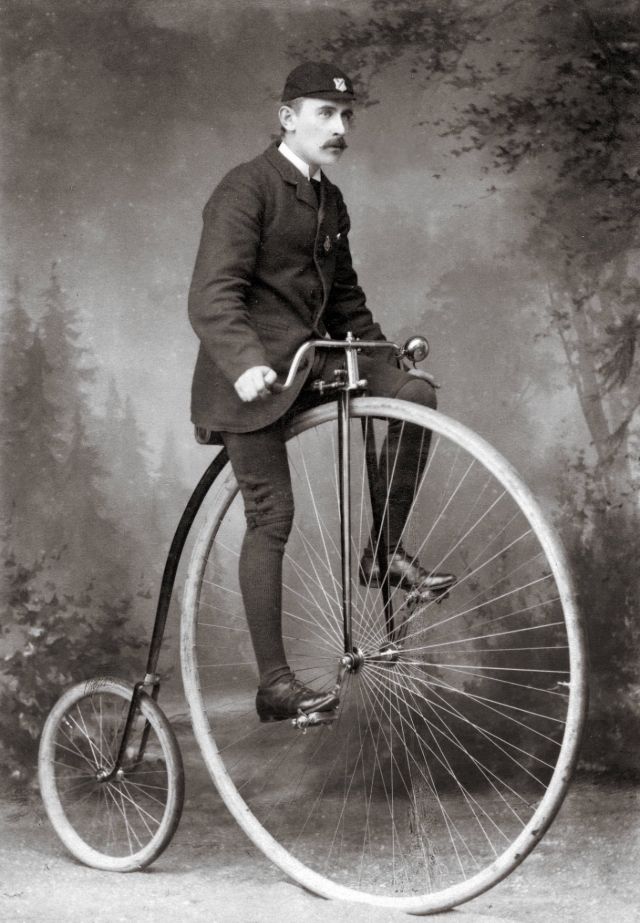

An attribute of the penny-farthing is that the rider sits high and nearly over the front axle.

An attribute of the penny-farthing is that the rider sits high and nearly over the front axle.

When the wheel strikes rocks and ruts, or under hard braking, the rider can be pitched forward off the bicycle head-first.

Headers were relatively common and a significant, sometimes fatal, hazard.

Riders coasting down hills often took their feet off the pedals and put them over the tops of the handlebars, so they would be pitched off feet-first instead of head-first.

Penny-farthing became obsolete in the late 1880s with the development of modern bicycles, which provided similar speed, via a chain-driven gear train, and comfort, from the use of pneumatic tires.

Penny-farthing became obsolete in the late 1880s with the development of modern bicycles, which provided similar speed, via a chain-driven gear train, and comfort, from the use of pneumatic tires.

They were marketed as “safety bicycles” because of the greater ease of mounting and dismounting, the reduced danger of falling, and the reduced height to fall, in comparison to penny-farthings.

Although the trend was short-lived, the penny-farthing became a symbol of the late Victorian era. Its popularity also coincided with the birth of cycling as a sport.

Frederick Lindley Dodds, of Stockton-on-Tees, England, is credited with having set the first hour record, covering an estimated distance of 15 miles and 1,480 yards (25.493 kms) on a high-wheeler during a race on the Fenner’s Track, Cambridge University on March 25, 1876.

The furthest (paced) hour record ever achieved on a penny-farthing bicycle was 22.09 miles (35.55 km) by William A. Rowe, an American, in 1886.

The record for riding from Land’s End to John o’ Groats on a penny-farthing was set in 1886 by George Pilkington Mills with a time of five days, one hour, and 45 minutes.

This record was broken in 2019 by Richard Thoday with a time of four days, 11 hours and 52 minutes.

From its birth in the inventive minds of engineers to its heyday as a societal status symbol, the penny-farthing’s journey reflects the dynamic interplay between innovation, fashion, and practicality.

So, the next time you spot one of these towering relics in a museum or a vintage photograph, let it be a reminder of an audacious era when bicycles reached new heights—quite literally.

The penny-farthing may have rolled into the shadows, but its legacy continues to spin a wheel of fascination in cycling history.

Penny-Farthing

Penny-Farthing

Penny-Farthing

Penny-Farthing

Penny-Farthing

Penny-Farthing

Penny-Farthing

Penny-Farthing

Penny-Farthing

Penny-Farthing

Penny-Farthing

Penny-Farthing

Penny-Farthing

Penny-Farthing

Penny-Farthing

Penny-Farthing

Penny-Farthing

Penny-Farthing

Penny-Farthing

Penny-Farthing

Penny-Farthing

Penny-Farthing

Penny-Farthing

Penny-Farthing

Penny-Farthing

Penny-Farthing

Penny-Farthing

Penny-Farthing

Penny-Farthing

Penny-Farthing

Penny-Farthing

Penny-Farthing

Penny-Farthing

(Photo credit: Pinterest / Flickr / Wikimedia Commons).