The Terra Nova Expedition, officially the British Antarctic Expedition, was an expedition to Antarctica which took place between 1910 and 1913. It was led by Robert Falcon Scott and had various scientific and geographical objectives. Pictured: The Terra Nova.

In 1910, British explorer Robert Falcon Scott led a privately funded expedition to become the first people to successfully reach the South Pole.

The expedition was Scott’s attempt to be the first to reach the South Pole, as well as carry out important scientific research along the coast of Victoria Land on the Ross Ice Shelf.

The scientific work was considered by chief scientist Wilson as the main work of the expedition, though Scott felt that the main objective was to reach the South Pole, and to secure ‘for the British Empire the honor of this achievement’ of reaching the remotest place on earth, and its southernmost point, first.

An Adélie penguin wanders across the pack ice in the Ross Dependency. 1910.

Scott’s previous Discovery expedition had seen him return as a hero for having reached the furthest south, and he had similar ambitions to reach the Pole first, perhaps at any cost.

The expedition would use the Terra Nova supply ship to guide them on the initial portion of the journey. Because of the name of the ship, Scott’s mission has been historically referred to as the Terra Nova Expedition.

Men and sled dogs on the Terra Nova, bound for Antarctica. 1910.

First Officer Victor Campbell took six men and sailed the Terra Nova east, hoping to carry out scientific work in King Edward VII Land. On the way back to camp, they stumbled upon a surprise — Roald Amundsen’s expedition had arrived and was camped in the Bay of Whales.

The two parties exchanged pleasantries, and Campbell hastened back to camp to inform Scott that his rival had arrived. Though dismayed by this development, Scott decided to proceed as planned and begin laying supply depots farther and farther into the interior of the continent in preparation for the push to the pole.

The mission encountered complications almost immediately. The party was held up by fierce blizzards. The ponies, who had performed much worse than expected, began weakening and dying. Only two of the eight ponies on the depot-laying mission made it back.

Meanwhile, parties of geologists explored the surrounding areas, surveying uncharted regions and collecting samples and specimens.

The 25 men of the shore party hunkered down in the hut with the beginning of the Antarctic winter in April 1911, passing the time with lectures, scientific studies and the occasional soccer match. Scott continued his calculations and planning for the journey to the pole.

Able seaman Mortimer McCarthy at the wheel of the Terra Nova. 1910.

Members of the party would turn back at specific latitudes, leaving a final group of five to reach the pole. The group with the motor sledges set out on October 24, 1911. The sledges broke down after about 50 miles. Without them, Scott had to adjust his plan and make the dogs push on.

The dogs were sent back to base, and on January 3, 1912, Scott selected the four men who would join him in the polar party: Chief Scientist Dr. Edward Wilson, Lawrence Oates, Henry Bowers and Edgar Evans. The final five men pushed southward.

On January 16, amid the endless expanse of white nothingness around them, they spotted something — a black flag fluttering from a sledge runner. A note was attached.

Crestfallen, Scott and his companions reached the South Pole the next day, and discovered the camp that Amundsen had left behind the day after that.

Though not the triumph they had envisioned, their mission was complete. Scott wrote in his diary: ‘The POLE. Yes, but under very different circumstances from those expected. Great God! This is an awful place and terrible enough for us to have laboured to it without the reward of priority.’

Ship’s surgeon George Murray Levick skins a penguin on the deck of the Terra Nova. 1910.

On 19 January 1912 the deflated group began their 800 mile (1,300 km) return journey. After a good start they began to suffer from slow starvation, hypothermia and scurvy. Even so, they stayed true to their scientific quest, taking geology samples whenever possible.

The final demise of the men was harrowing, amid worsening weather conditions. Edward Evans died on 17 February at the base of Beardmore Glacier, having fallen and suffered damage to his head. Captain Oates had severe frostbite and walked out into the cold to the words, later recorded by Scott: ‘I am just going outside and may be some time…’, walking out into a blizzard to sacrifice his life so the other men could carry on unhindered.

In due course, having taken shelter in tents and written farewell messages to their family, Scott and his two surviving comrades, Bowers and Wilson, perished from most likely starvation and exposure to the extreme cold. Their bodies were found 8 months later.

The last entry in Scott’s diary on 29 March 1912 read: “Every day we have been ready to start for our depot 11 miles away, but outside the door of the tent it remains a scene of whirling drift. I do not think we can hope for any better things now. We shall stick it out to the end, but we are getting weaker, of course, and the end cannot be far. It seems a pity but I do not think I can write more. R. Scott. Last entry. For God’s sake look after our people”.

Back at camp, the other members of the expedition made numerous trips to supply depots in hopes of catching the polar party, to no avail. After wintering in the hut, a search party set out on October 29. Less than two weeks later they found the bodies of Scott, Wilson and Bowers. They built a stone cairn over them where they lay.

In 1913, Scott’s late wife, Kathleen, was made a widow of a Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath. Scott had not received a posthumous knighthood, and Kathleen was not entitled to be called Lady Scott, but she could be treated as if she were the widow of such a knight.

In July 1913, members of the expedition (Bowers, Oates, Wilson, Edgar Evans, Scott and Brissenden posthumously), were awarded the Polar Medal (silver or bronze) with clasp inscribed ‘Antarctic, 1910-1913’.

In the same year (1913), a wooden cross was erected on Observation Hill, Ross Island, inscribed with the names of the dead adventurers and the apt Tennyson quote,

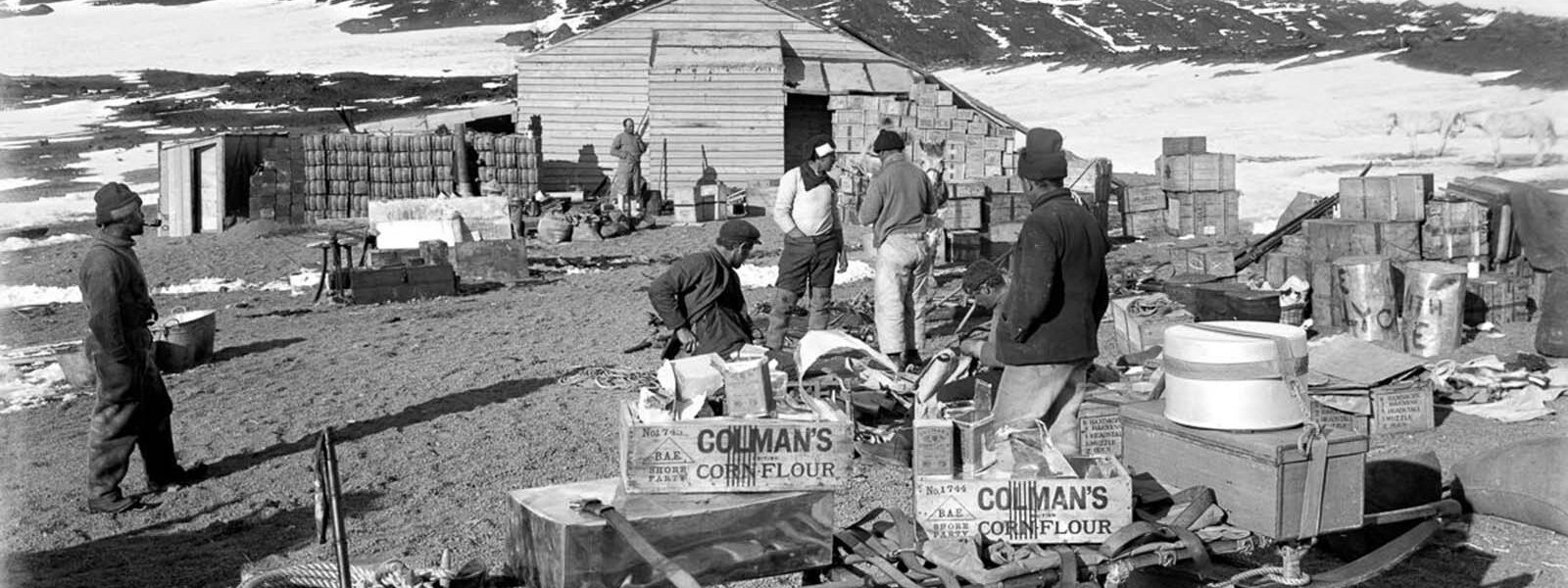

Men arrange supplies at the camp on Cape Evans, with active volcano Mt. Erebus in the background. Jan. 23, 1911.

Capt. Lawrence Oates tends to the ponies in their stables aboard the Terra Nova. December, 1910.

Geologist Thomas Griffith Taylor and meteorologist Charles Wright look out towards the Terra Nova from inside an ice grotto. January 5, 1911.

Chief Scientist Dr. Edward Wilson with Nobby the pony. The ponies were brought to haul sledges but proved ill-suited to the Antarctic climate and terrain. 1911.

A dog team rests by an iceberg. 1911.

The Terra Nova anchored in McMurdo Sound. 1911.

An Adélie penguin defends its nest from photographer Herbert Ponting at Cape Royds, Ross Island.

Chris the sled dog listens to a gramophone. 1911.

Petty Officer Edgar Evans. 1911.

Men heat up a meal on a camp stove. February 7, 1911.

Expedition cook Thomas Clissold leads an Emperor penguin by a rope. April 1, 1911.

Dr. Edward Wilson in a sledging outfit. April 1911.

An expedition member enjoys a can of beans at camp. January, 1912.

Capt. Scott and other expedition members pose at camp after returning from the depot-laying expedition. April, 1911.

Dog handler Cecil Meares and Capt. Lawrence Oates cook blubber for the dogs. May, 1911.

Capt. Scott, at the head of the table, celebrates his 43rd birthday. June 6, 1911.

Geologist Frank Debenham grinds stone samples. June 12, 1911.

Photographer Herbert Ponting in his makeshift darkroom. July 22, 1911.

A sledging party. 1912.

Apsley Cherry-Garrard looks on as Michael the pony rolls in the snow. October, 1911.

Capt. Scott writes in his diary in his quarters. Pictures of his wife and son adorn the wall behind him. October 7, 1911.

A man stands atop the Matterhorn Berg with active volcano Mt. Erebus in the background. October 8, 1911.

Men in “The Tenements.” Henry Robertson Bowers, Lawrence Oates, Cecil Meares and Edward L. Atkinson lie on bunks, while Apsley Cherry-Garrard stands on the left. October 9, 1911.

Anton Omelchenko stands at the end of the Barne Glacier on Ross Island. December 2, 1911.

Dog handler Cecil Meares at the piano in the hut. January, 1912.

Capt. Scott outfitted for his push to the South Pole. November 1911.

Capt. Scott leads a sledging party on a bid to reach the South Pole before Amundsen. January 1912.

A frostbitten Charles Wright at camp after returning from the Great Ice Barrier as part of the first support party aiding Scott’s push to the South Pole. January 1912.

Dr. Wilson, Capt. Scott, Capt. Oates, Henry Bowers and Edgar Evans pose at the South Pole. January 18, 1912.

Capt. Scott and the polar party discover a tent left behind by Amundsen, who had reached the South Pole a month earlier. January 18, 1912.

Expedition members return to New Zealand on the Terra Nova after finding the bodies of Scott and the other victims. January, 1913.

(Photo credit: Scott Polar Research Institute / University of Cambridge / Hulton-Deutsch Collection / Corbis via Getty Images)