Vintage photos show the spectacular engineering feat that brought drinking water to New York City, 1906-1917 _ US

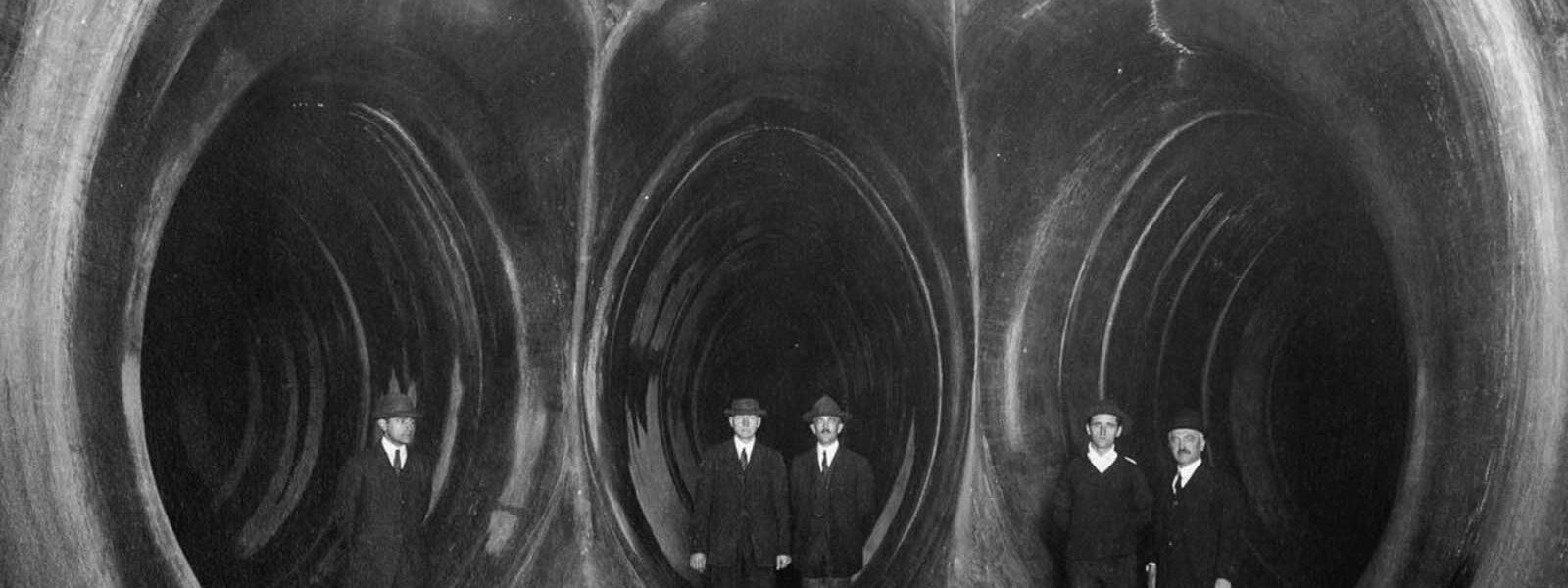

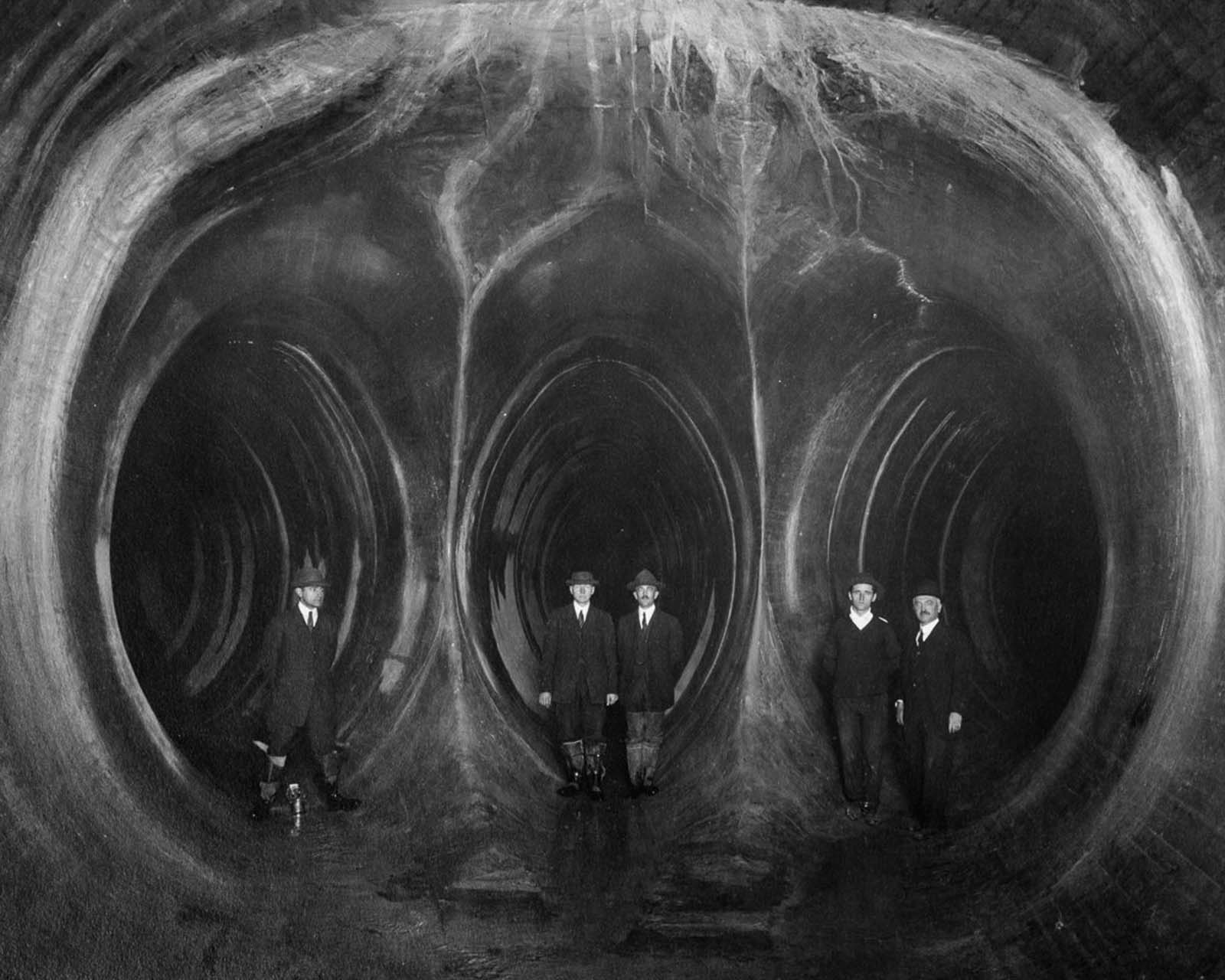

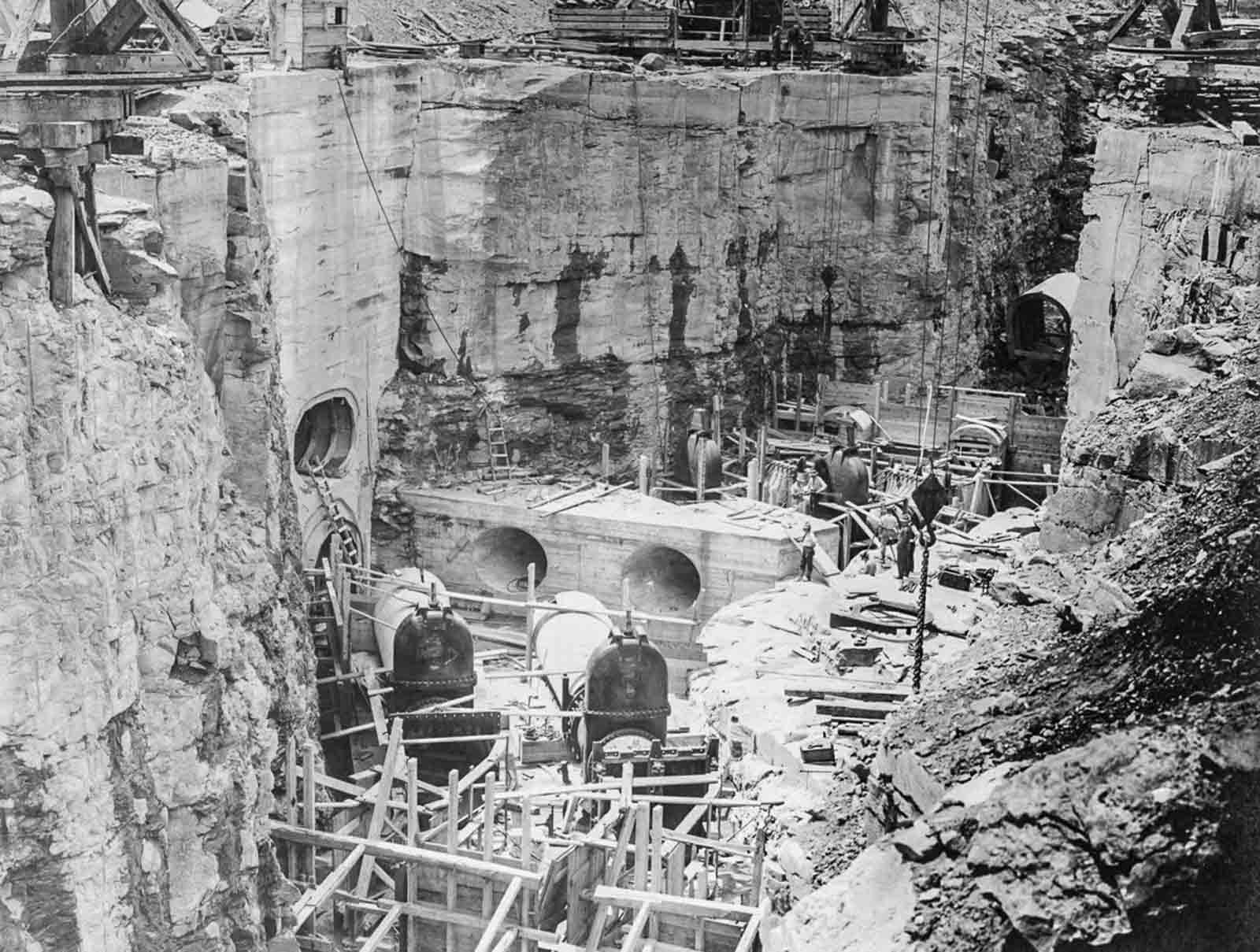

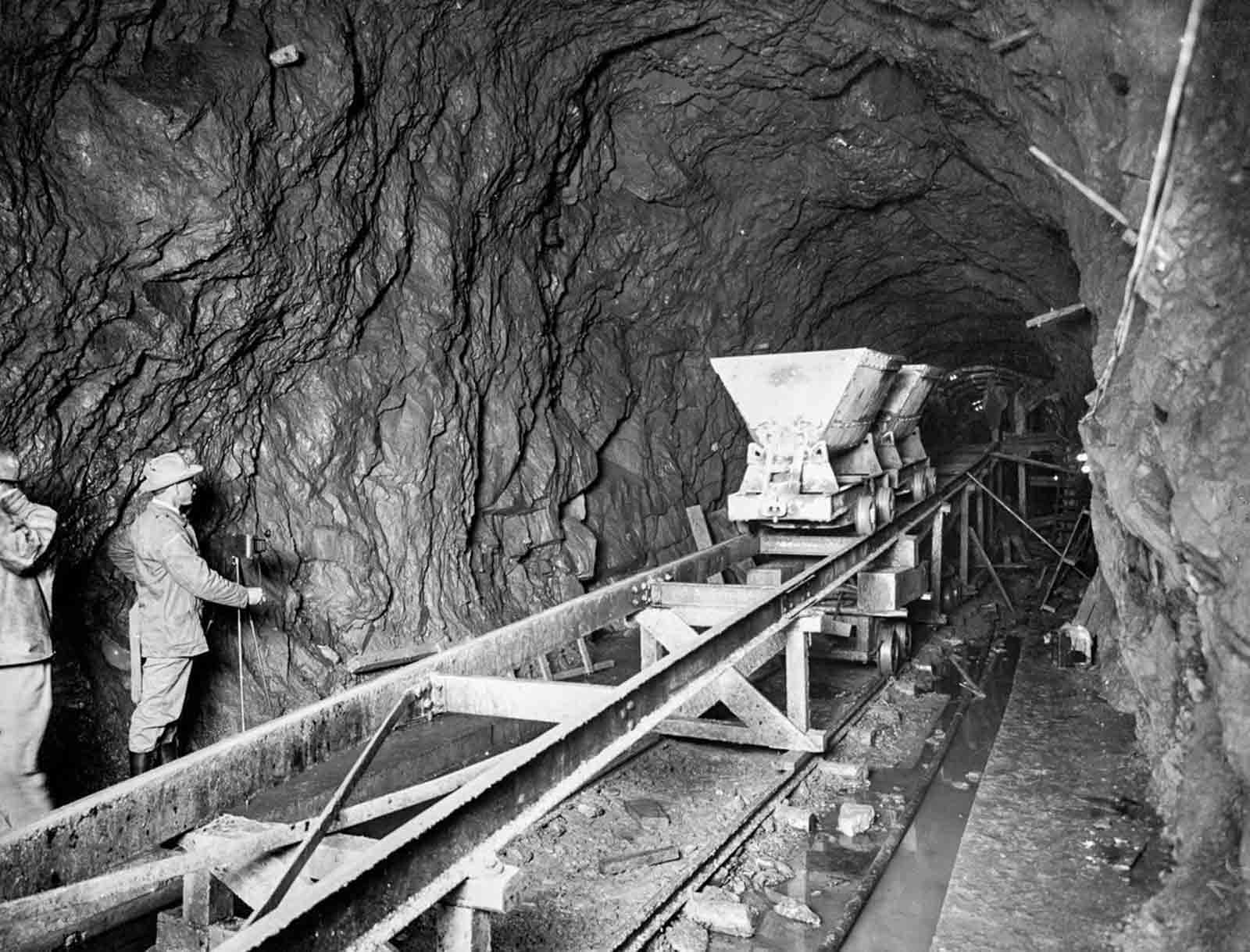

A fork in the Yonkers pressure tunnel. 1913.

These incredible vintage photos show how one of the world’s greatest engineering feats was created in 1906-1915 to bring water to New York City. In 1905, the city’s newly established Board of Water Supply launched the Catskill Aqueduct project, which would play an additional role in supplying the city’s ever-growing population of residents and visitors.

These projects rank as the greatest municipal water-supply enterprise ever undertaken, and as an engineering work is probably second only to the Panama Canal.

In 1898, Greater New York with a population of 3.5 million was formed through the consolidation of Manhattan, the Bronx, Queens, Brooklyn, and Staten Island. New York water engineers in the early decades of the twentieth century began to look further afield, to sources in the Catskill Mountains beyond the Hudson River.

The area in question was formerly a farming area, with logging activity as well as the quarrying of bluestone. Over two thousand people were relocated, including a thousand New Yorkers with second homes. 32 cemeteries were unearthed and the 1,800 residents buried elsewhere, to limit water contamination. Residents were offered $15 from the city disinter their relatives and rebury them elsewhere.

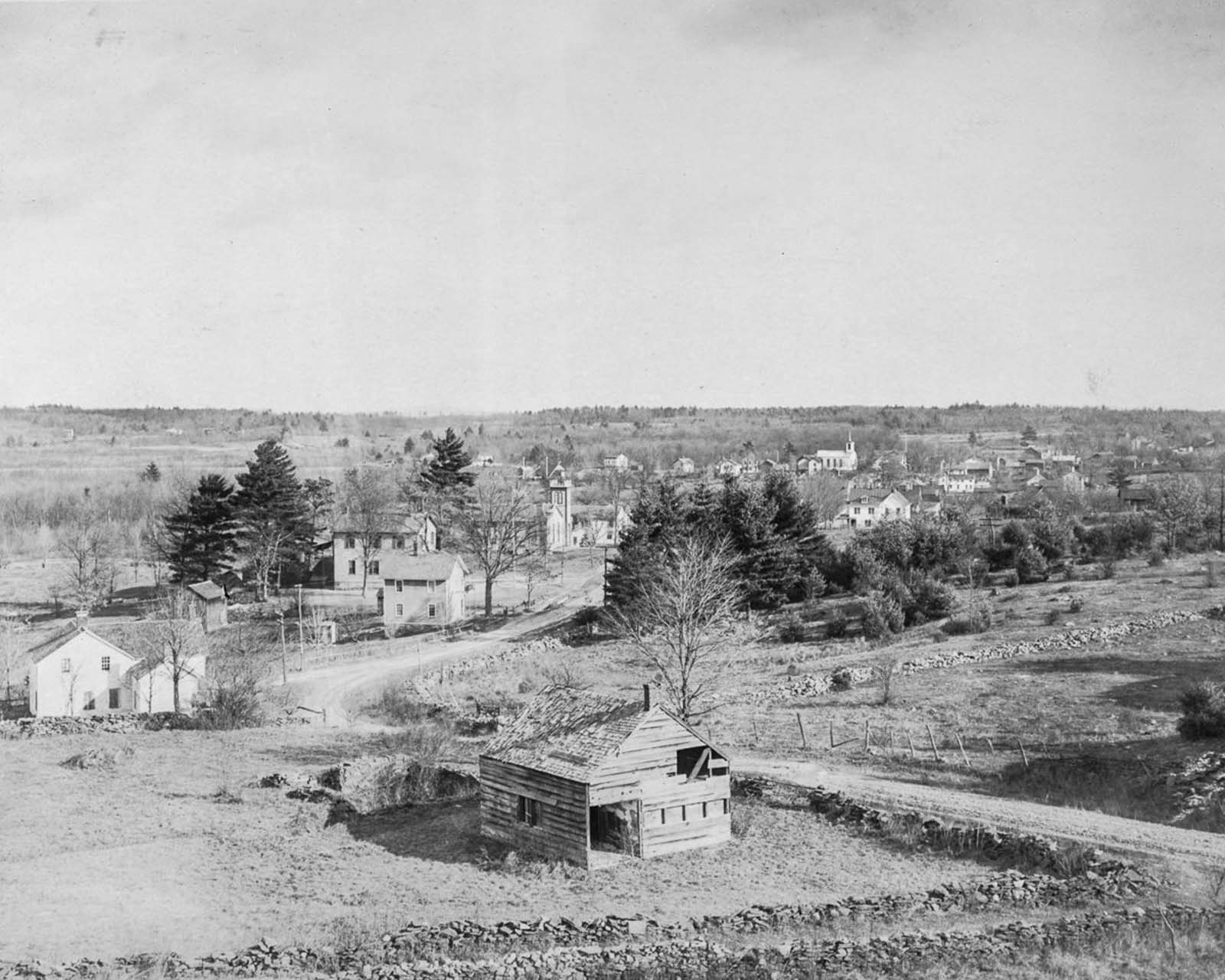

The village of Shokan, which lies within the territory claimed for the west basin of the Ashokan Reservoir. 1906.

Buildings and industries were relocated or burned down, trees and brush were removed from the future reservoir floor–all the work done predominantly by local laborers, African-Americans from the south and Italian immigrants.

Officially the construction of the new water supply commenced in 1907. The aqueduct proper was completed in 1916 and the entire Catskill Aqueduct system including three dams and 67 shafts was completed in 1924. The total cost of the aqueduct system was $177 million ($2.4 billion in 2015 dollars).

The 92-mile (148 km) aqueduct consists of 55 miles (89 km) of cut and cover aqueduct, over 14 miles (23 km) of grade tunnel, 17 miles (27 km) of pressure tunnel, and nine miles (10 km) of steel siphon.

The 67 shafts sunk for various purposes on the aqueduct and City Tunnel vary in depth from 174 to 1,187 feet (362 m). Water flows by gravity through the aqueduct at a rate of about 4 feet per second (1.2 m/s).

The town of West Hurley, which was included in the territory taken for the east basin of the Ashokan Reservoir. 1906.

In 1914, the wings of the dam were terraced with three- to four-ton blocks of bluestone quarried locally, and 780 men and 244 mules and horses laid macadam over the 40 miles of reservoir roads. The local water was so pure that New Yorkers had long been buying it in five-gallon carboys from the Crystal Spring Water Company of Pine Hill.

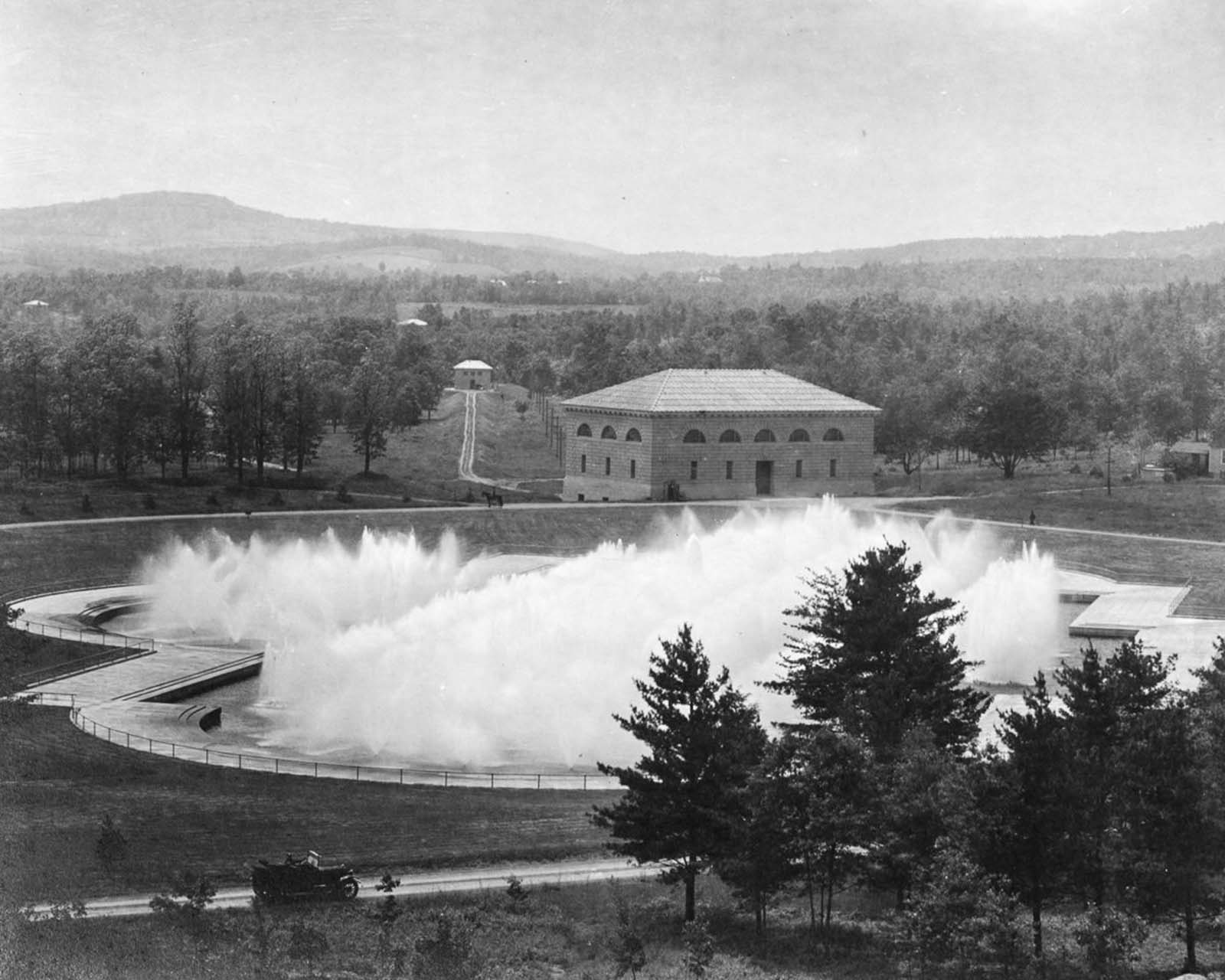

So the facility did not need a filtration plant, but was instead given an aerating fountain. Water passed through an aeration basin, a small reservoir 500 by 250 feet, its bottom lined with pipes four or five feet apart, from which streams were ejected 40 to 60 feet in the air.

This oxidized vegetable organisms and removed taste and odor. (Eventually alum was introduced to counter the effects of turbidity and soda ash to prevent over-acidity, and the water was chlorinated twice, at the Kensico and Hillview Reservoirs.)

On June 24, 1914, all the steam whistles in the zone were set off at once, marking the official end of the project. Only the cleanup remained. Throughout 1916, workers slowly demolished the camp at Brown’s Station and the plants and temporary railroads.

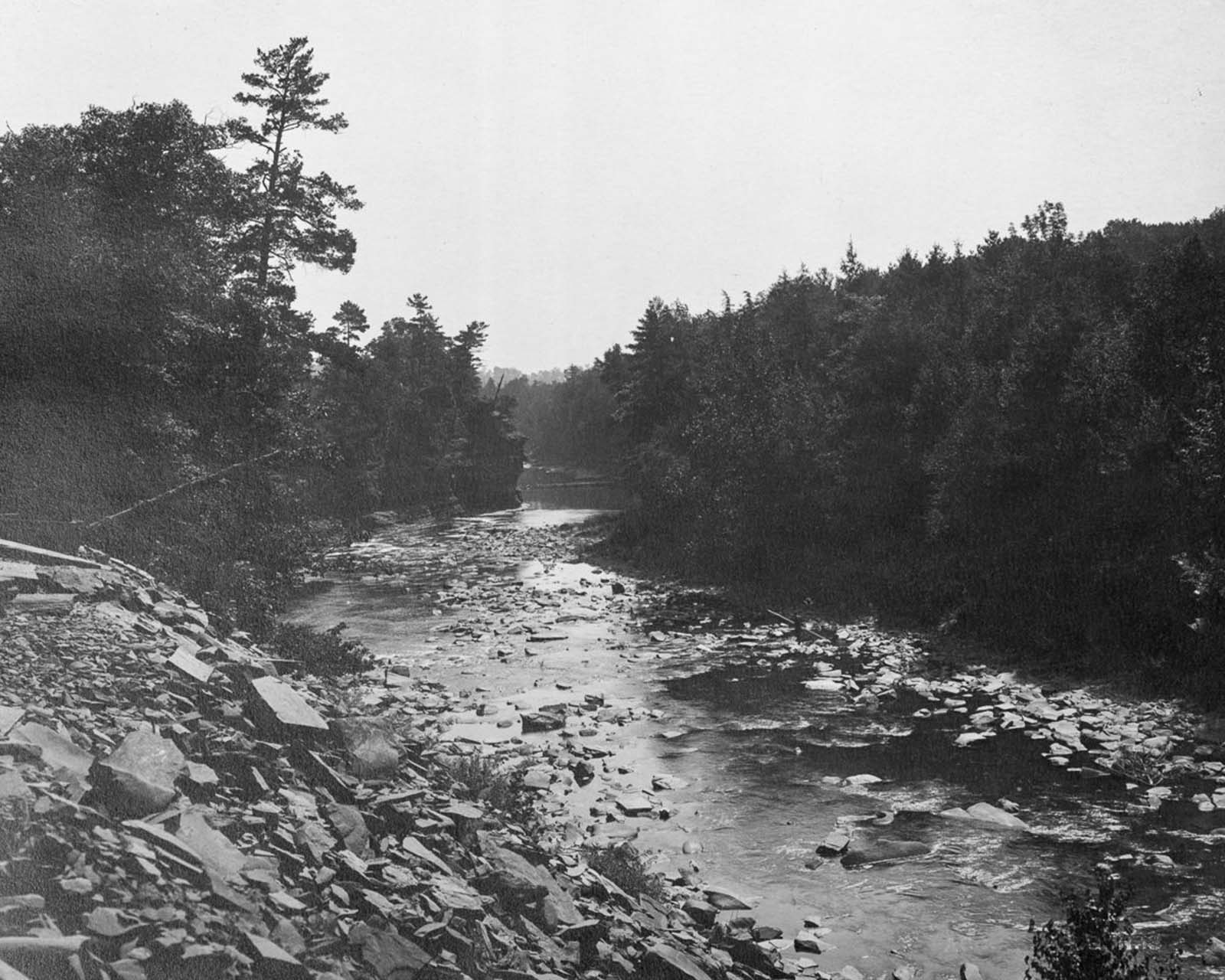

The chosen site of the Olive Bridge Dam in Esopus Creek. 1906.

The year 1914 had been dry, but in 1915 the rains came, filling the reservoir to a hundred feet; on November 22, water was released into the aqueduct. The project was rivaled only by the Panama Canal as an achievement of America’s engineering might.

The Ashokan Reservoir had the potential to deliver 660 million gallons a day. The reservoir’s surface was equal to that of Manhattan below 110th Street. Its contents could fill the Hudson River from the Battery at the southern tip of Manhattan to Hastings-on-Hudson in Westchester County.

It took three days for a theoretical drop to travel from the Catskills to Staten Island, which received its first Ashokan water in January 1917.

In October 1917, New York City held a three-day celebration of its new water supply, during which 15,000 schoolchildren and a thousand women from Hunter College participated in a pageant in Central Park called “The Good Gift of Water.” As additions to the original, Schoharie Reservoir and Shandaken Tunnel was put into use 13 years later in 1928.

Nowadays, the Catskill Aqueduct has an operational capacity of about 550 million US gallons (2,100,000 m3) per day north of the Kensico Reservoir in Valhalla, New York. Capacity in the section of the aqueduct south of Kensico Reservoir to the Hillview Reservoir in Yonkers, New York is 880 million US gallons (3,300,000 m3) per day.

The aqueduct normally operates well below capacity with daily averages around 350–400 million US gallons (1,500,000 m3) of water per day. About 40% of New York City’s water supply flows through the Catskill Aqueduct.

Piers are built in the bed of Esopus Creek to support pipes to carry the flow of water. 1907.

Esopus creek at the Olive Bridge dam site, showing coffer-dams and two lines of 8-foot steel pipes for carrying the flow of the creek. 1907.

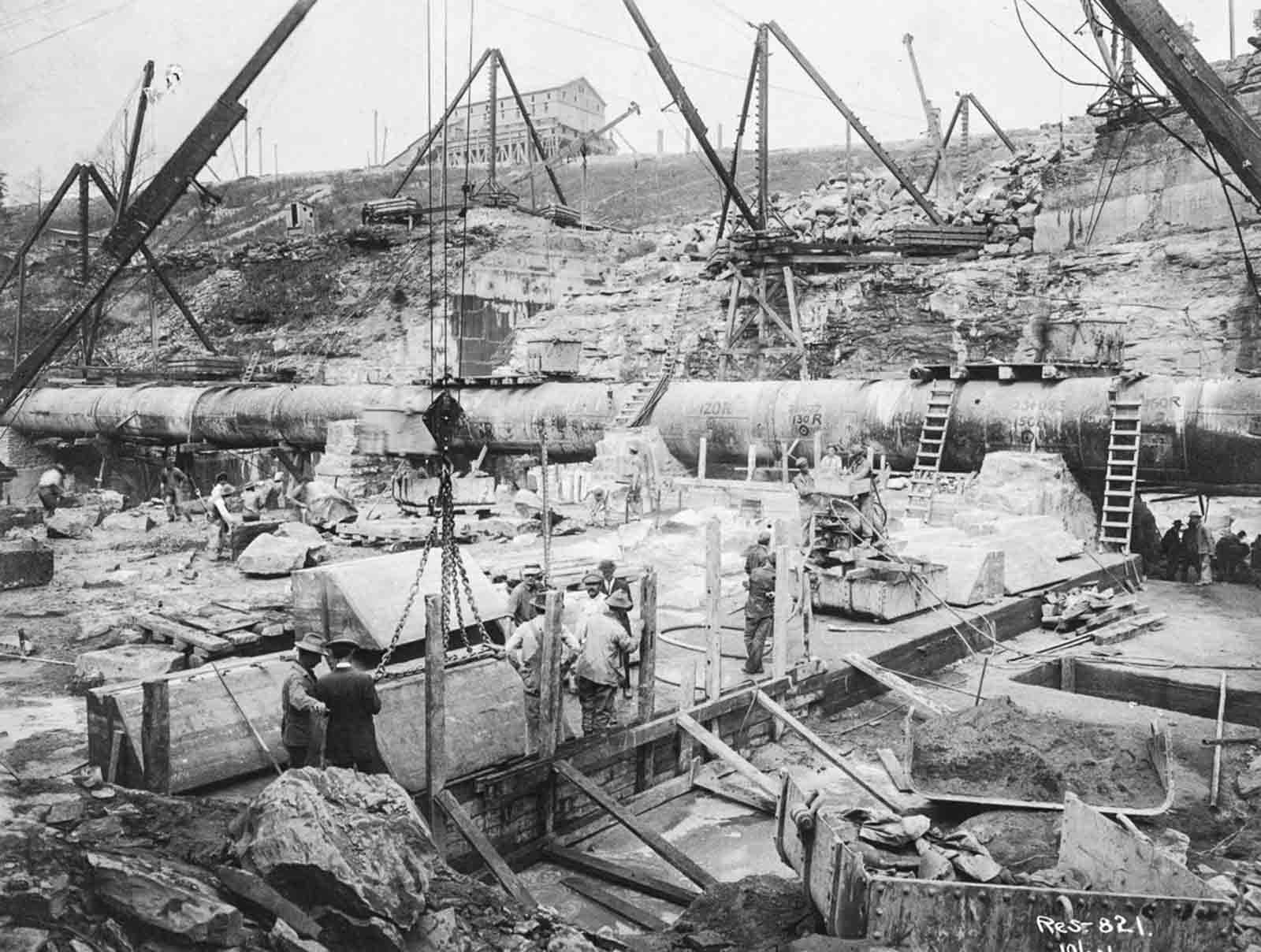

Work in progress on the cut-off trench under the masonry portion of the Olive Bridge Dam. 1908.

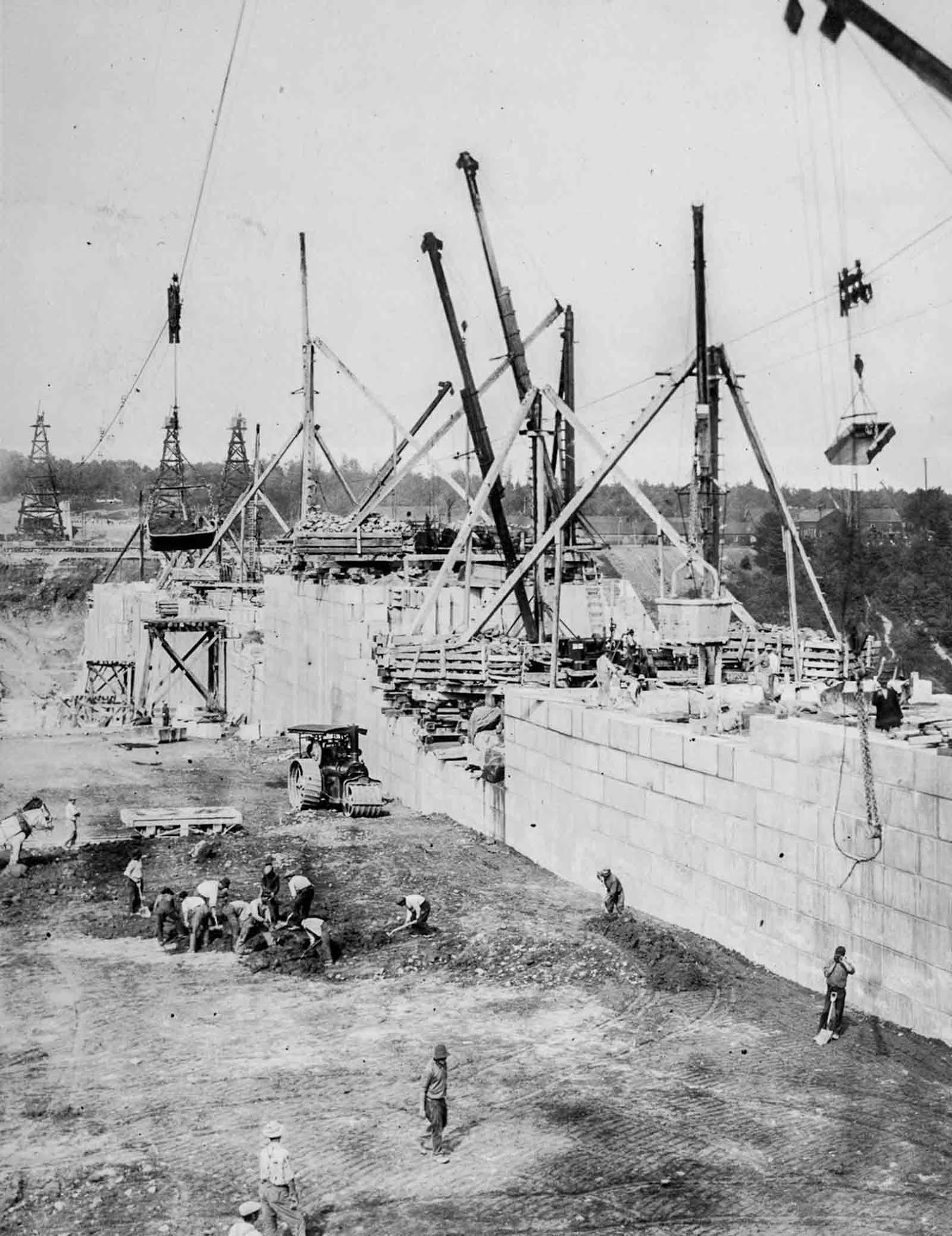

The first concrete block is placed on the downstream face of the Olive Bridge dam. 1908.

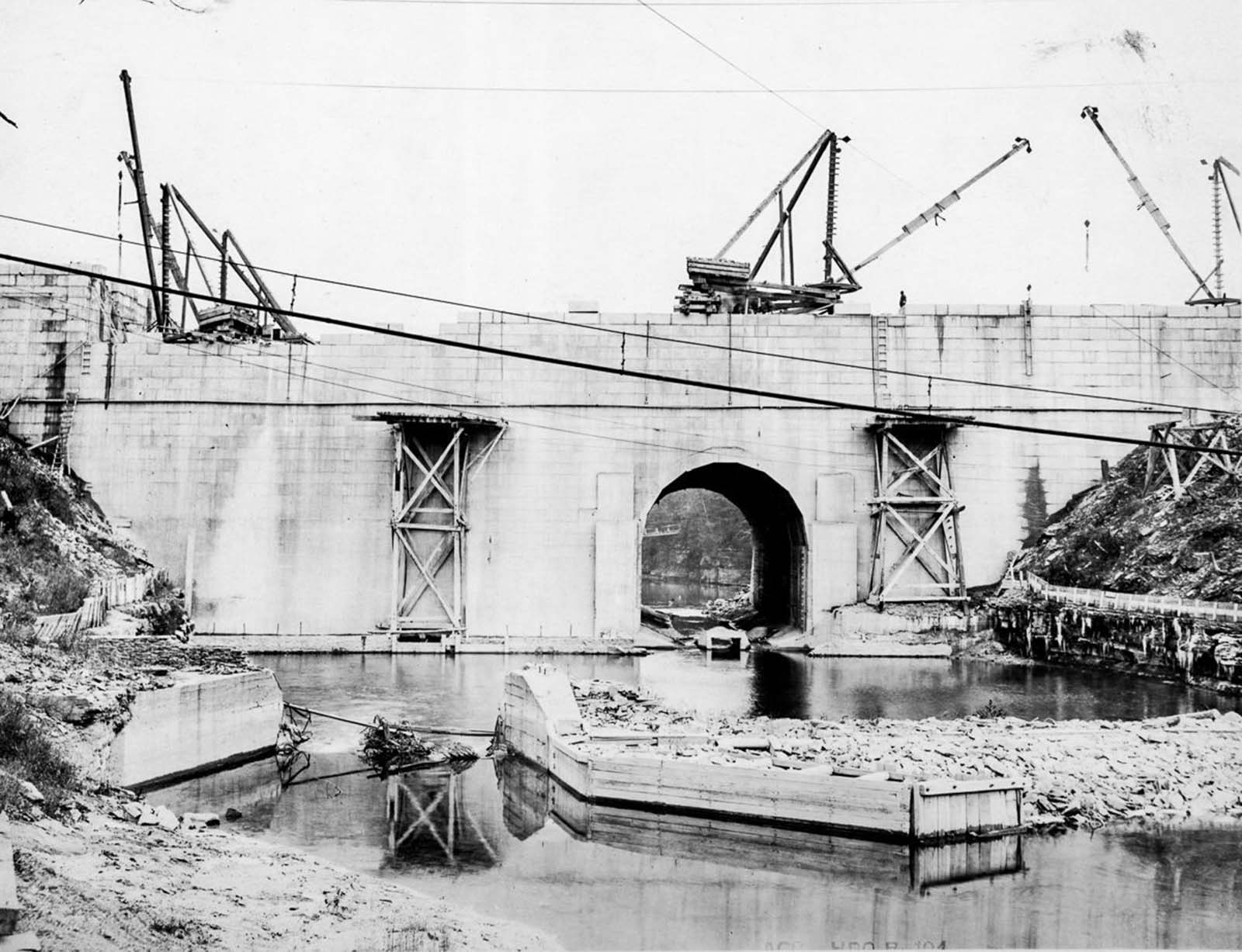

The upstream stream face of the masonry portion of Olive Bridge dam with a temporary opening for the flow of Esopus creek. 1909.

Ashokan Reservoir workers in camp. 1910.

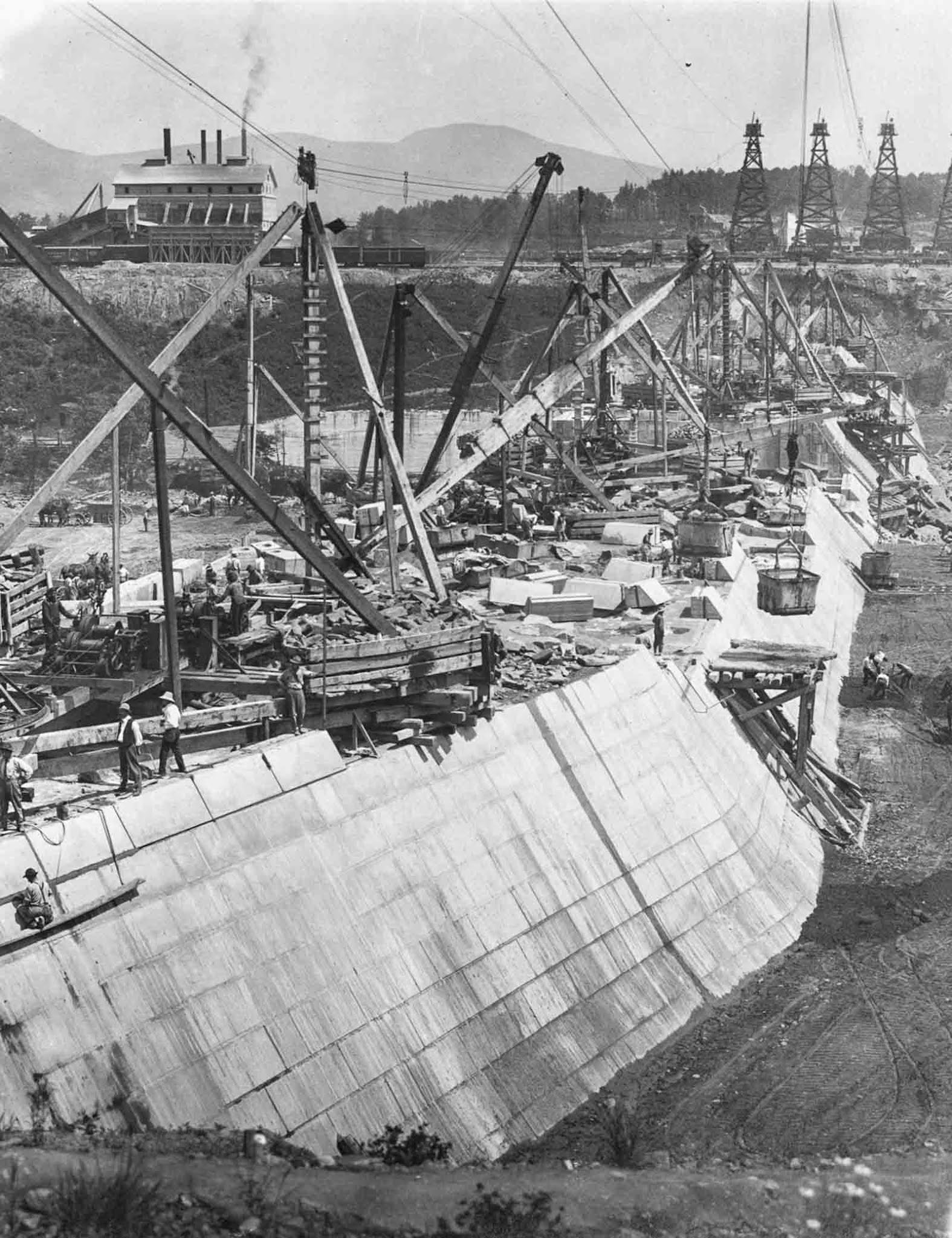

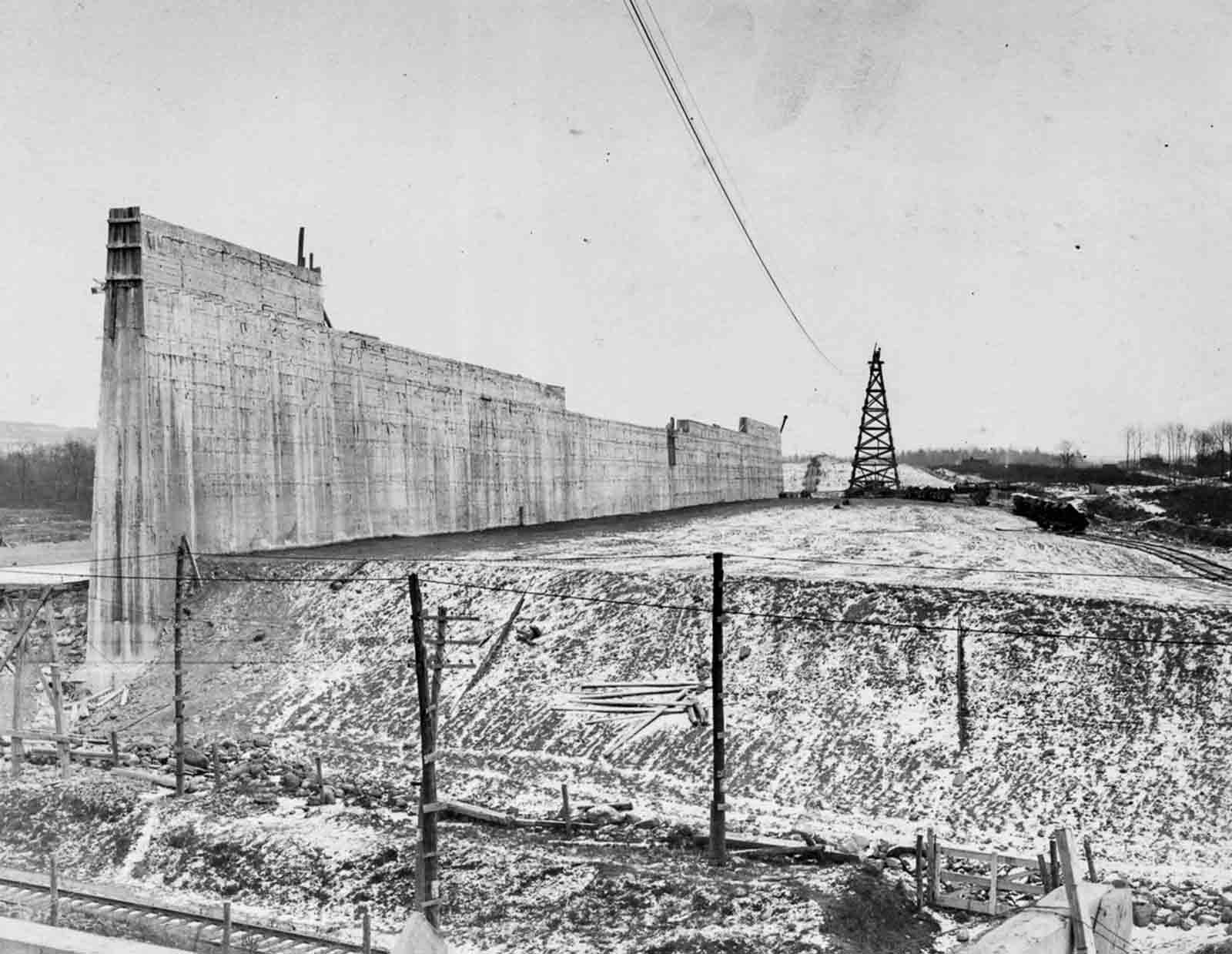

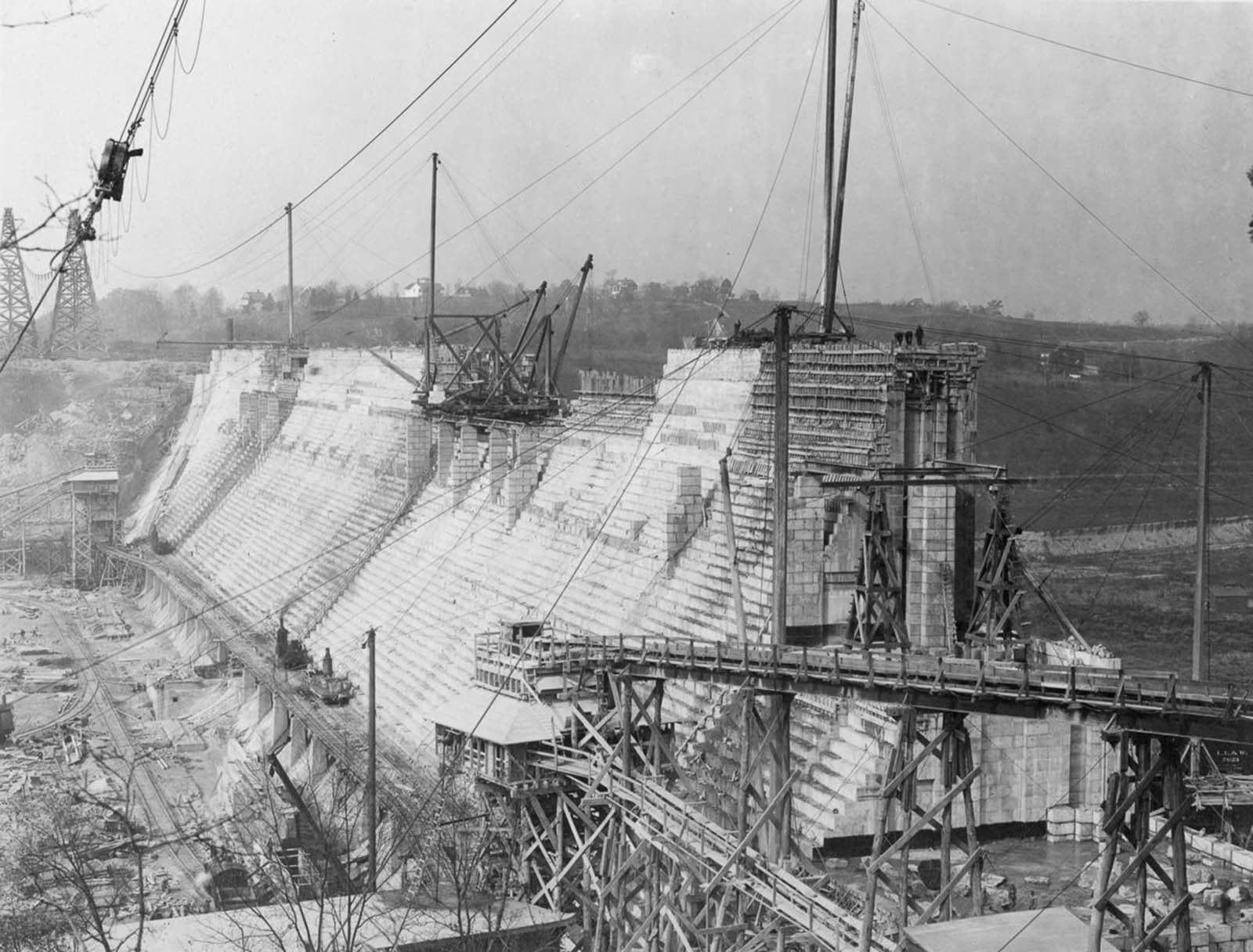

The downstream face of the Olive Bridge Dam under construction. 1910.

An earthen embankment is placed and compacted with a steamroller on the upstream face of the Olive Bridge Dam. 1910.

The downstream face of the Olive Bridge dam. 1911.

The Ashokan Reservoir’s upper gate-chamber from the East Inlet channel, with aqueducts for drawing water from the reservoir.

Earth is dumped into the reservoir on the upstream face of the Olive Bridge Dam. 1914.

The concrete core-wall of the Ashokan Reservoir’s middle dike. 1910.

Earth is dumped to form an embankment against the west dike of the Ashokan Reservoir. 1910.

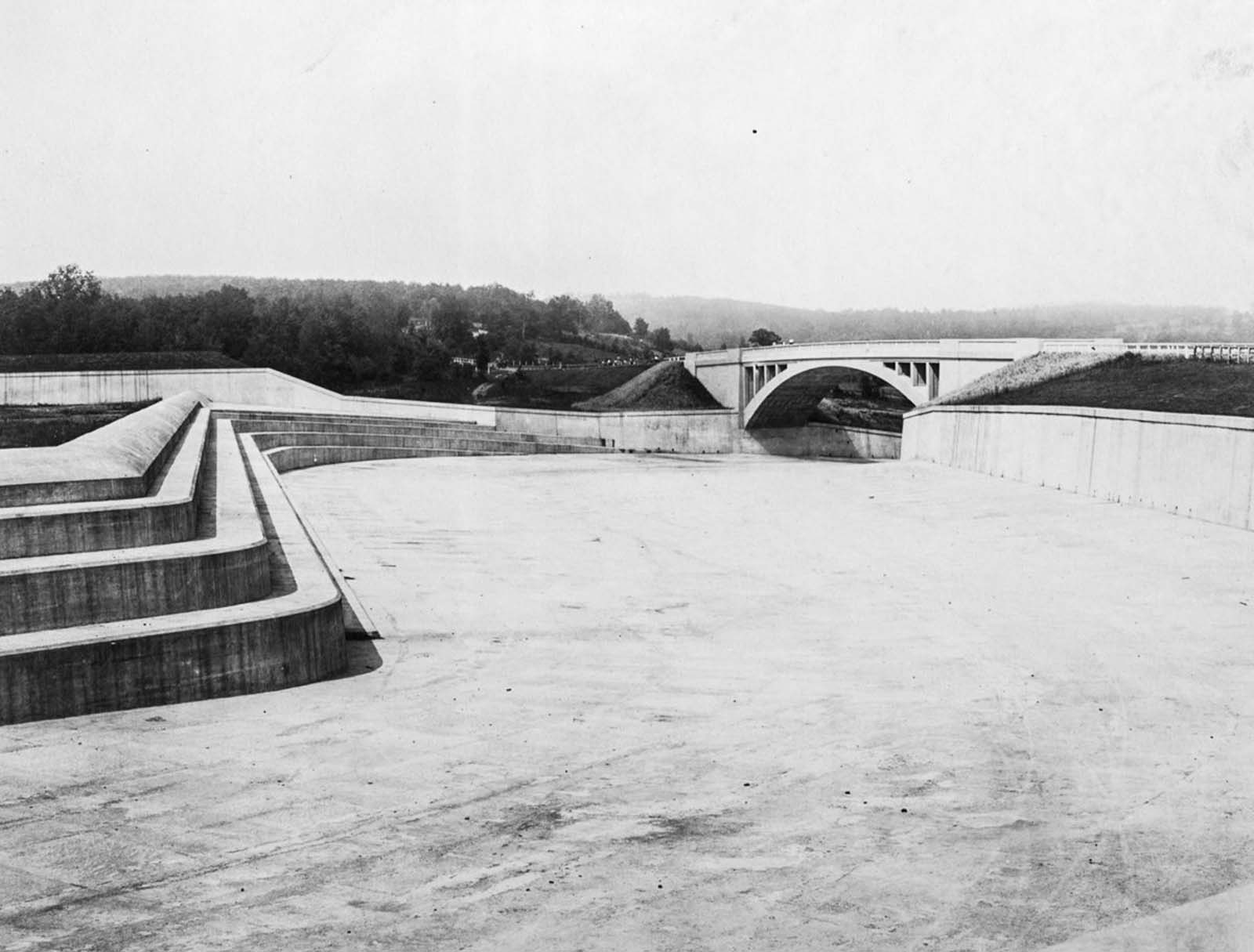

The inlet and gate house between the two basins of the Ashokan Reservoir, with two arches of the Ashokan Bridge in progress. 1914.

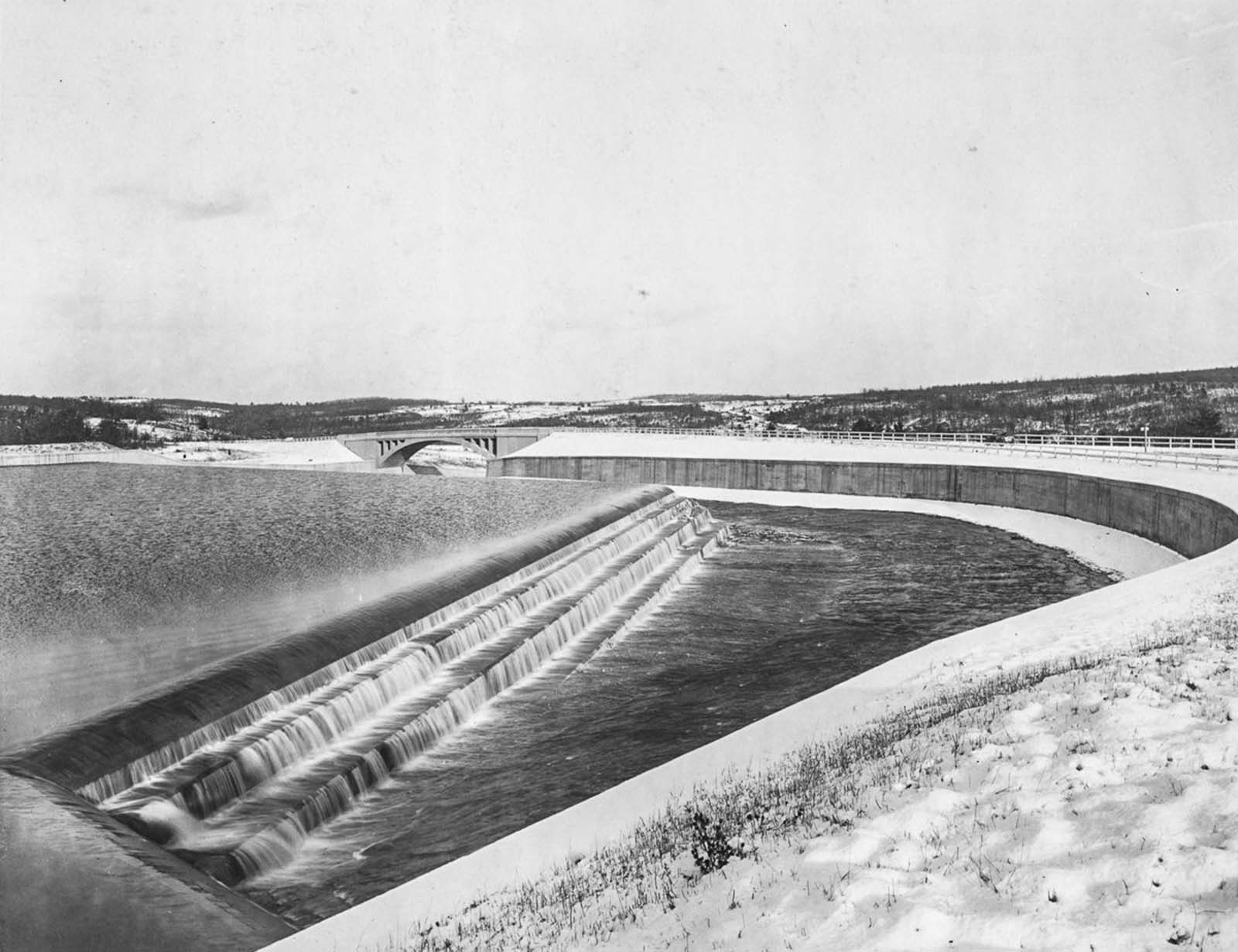

The Ashokan Reservoir’s waste weir and spillway. 1914.

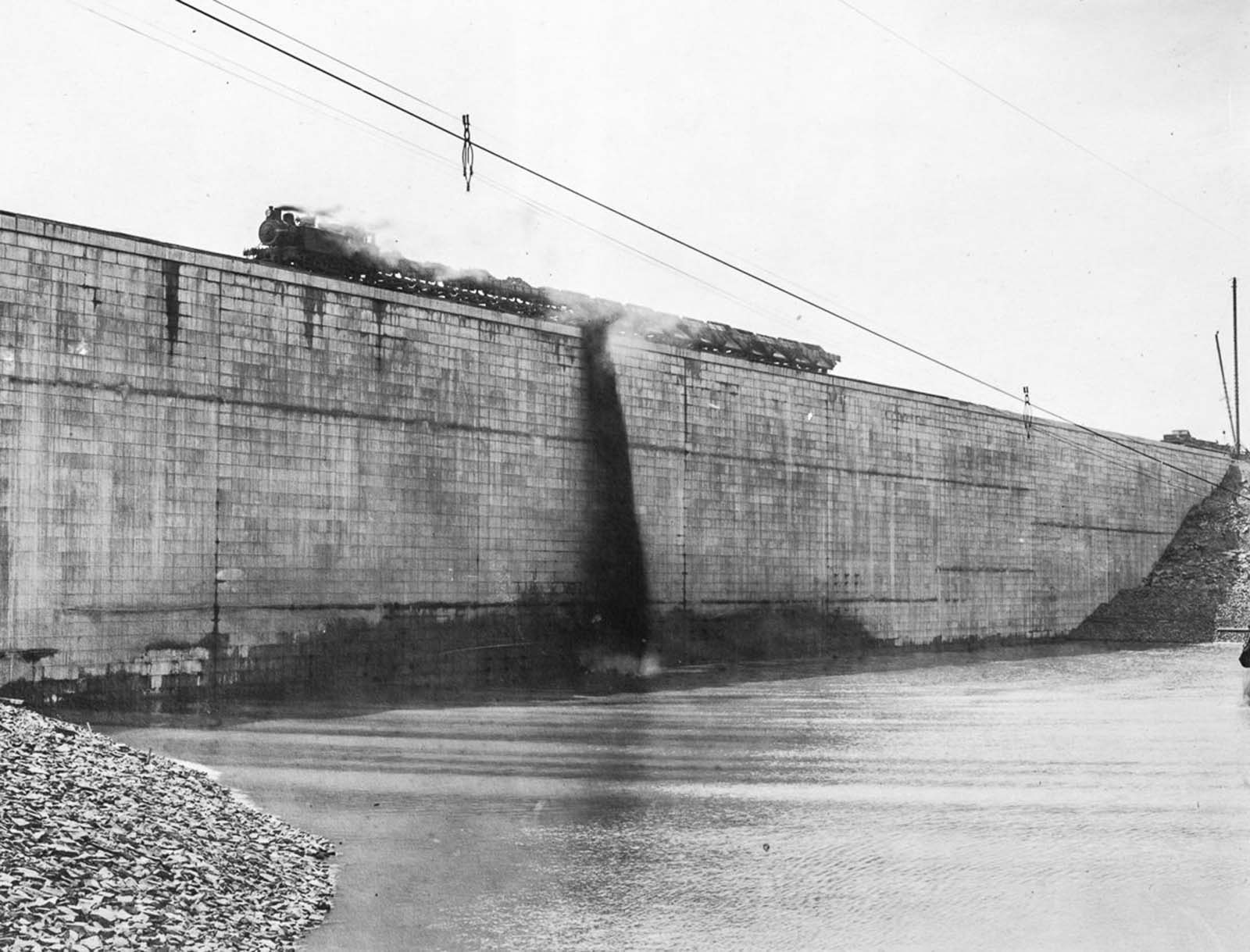

A train crosses the Glenford dike next to the east basin of the Ashokan Reservoir.

The Ashokan Reservoir’s waste weir and spillway leading to Esopus creek.

The excavation of the old Kensico Dam in preparation for the construction of a replacement.

The excavation for the foundation of the Kensico Dam in progress. 1912.

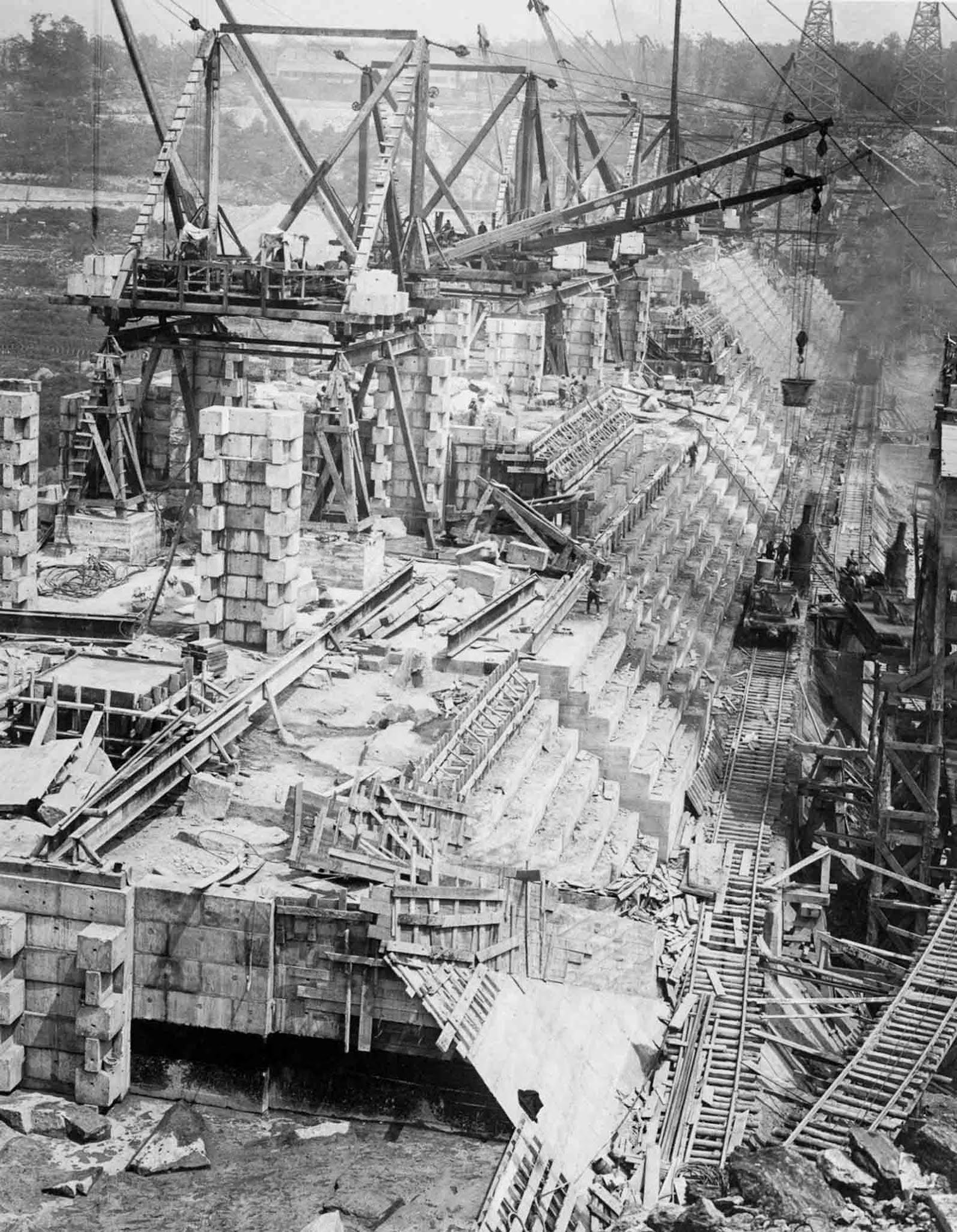

Travelling derricks place concrete blocks on the downstream face of the Kensico Dam. 1913.

Derricks maneuver concrete blocks into place on the Kensico Dam. 1914.

Inside the completed Kensico screen chamber. 1914.

The downstream face of the Kensico Dam. 1914.

A decorative granite facade is applied to the downstream face of the Kensico Dam. 1915.

The east pylon of the Kensico Reservoir, with its fountain and cascade basin. 1917.

Concrete lining is applied to the bottom of the Hillview Reservoir in Yonkers. 1914.

An aqueduct pipe under construction with a “cut-and-cover” method. 1910.

A work crew on a stretch of “cut-and-cover” aqueduct.

The Kensico Bypass Aqueduct. 1910.

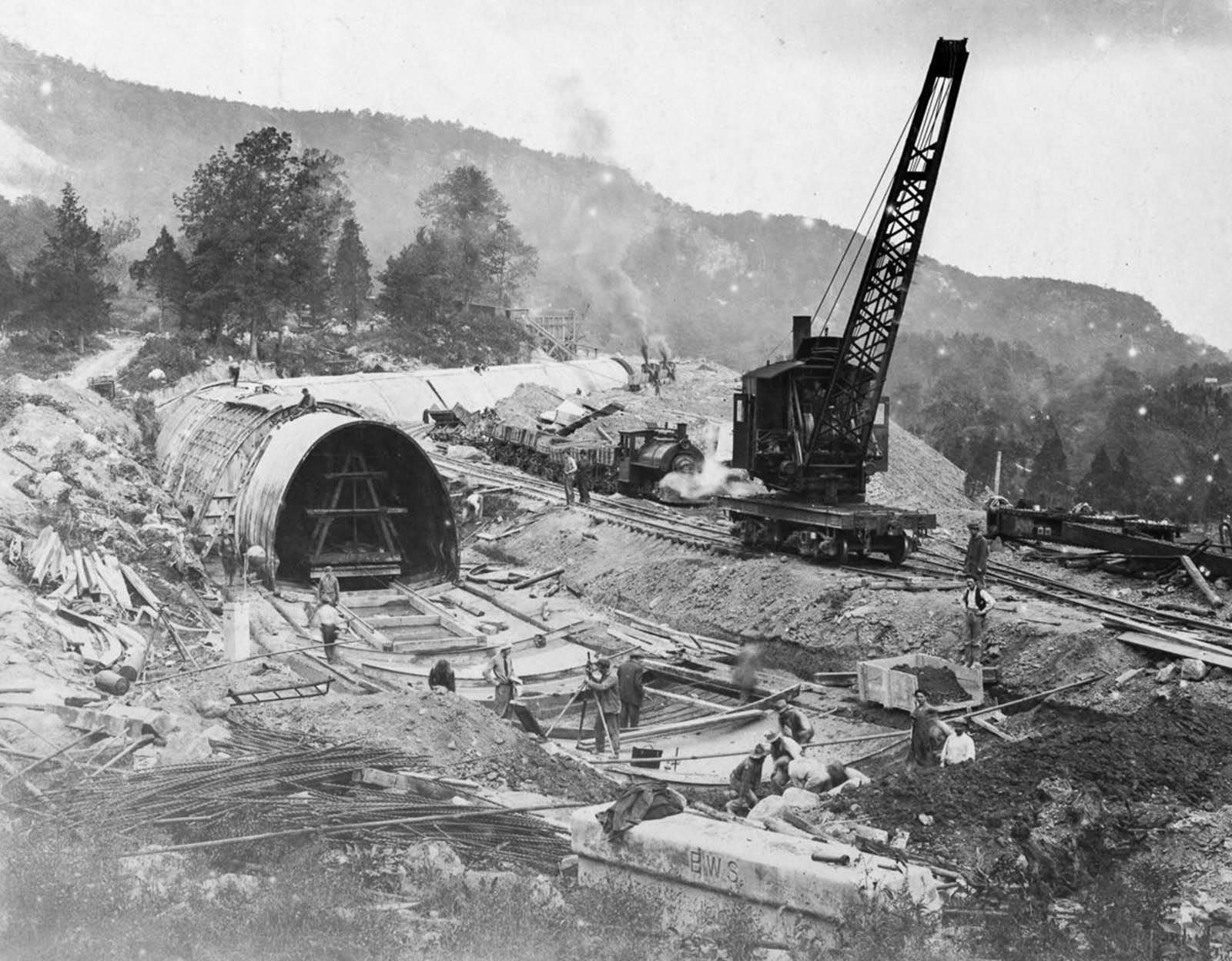

The excavation of the Bonticou Tunnel in progress. 1911.

The Garrison Tunnel in the process of timbering and bench mucking. 1911.

Drills bore into the bed of the Hudson River at Storm King Mountain, where the Catskill Aqueduct crosses from the west side of the river to the east, 1,100 feet underground. 1907.

The top of Shaft 7 of the Moodna pressure tunnel, with the Hudson River in the background. 1910.

A surveyor takes cross-section measurements with a sunflower instrument in the City tunnel south of Shaft 16. 1913.

Inside the Rondout pressure tunnel. 1911.

A section of the Rondout pressure tunnel with finished concrete lining in place. 1910.

Pressure valves inside the Catskill Aqueduct.

Inside a completed 16-foot, 7-inch-diameter section of the Yonkers pressure tunnel. 1917.

The Ashokan screen chamber aerates the daily flow of 376 million gallons of water. 1917.