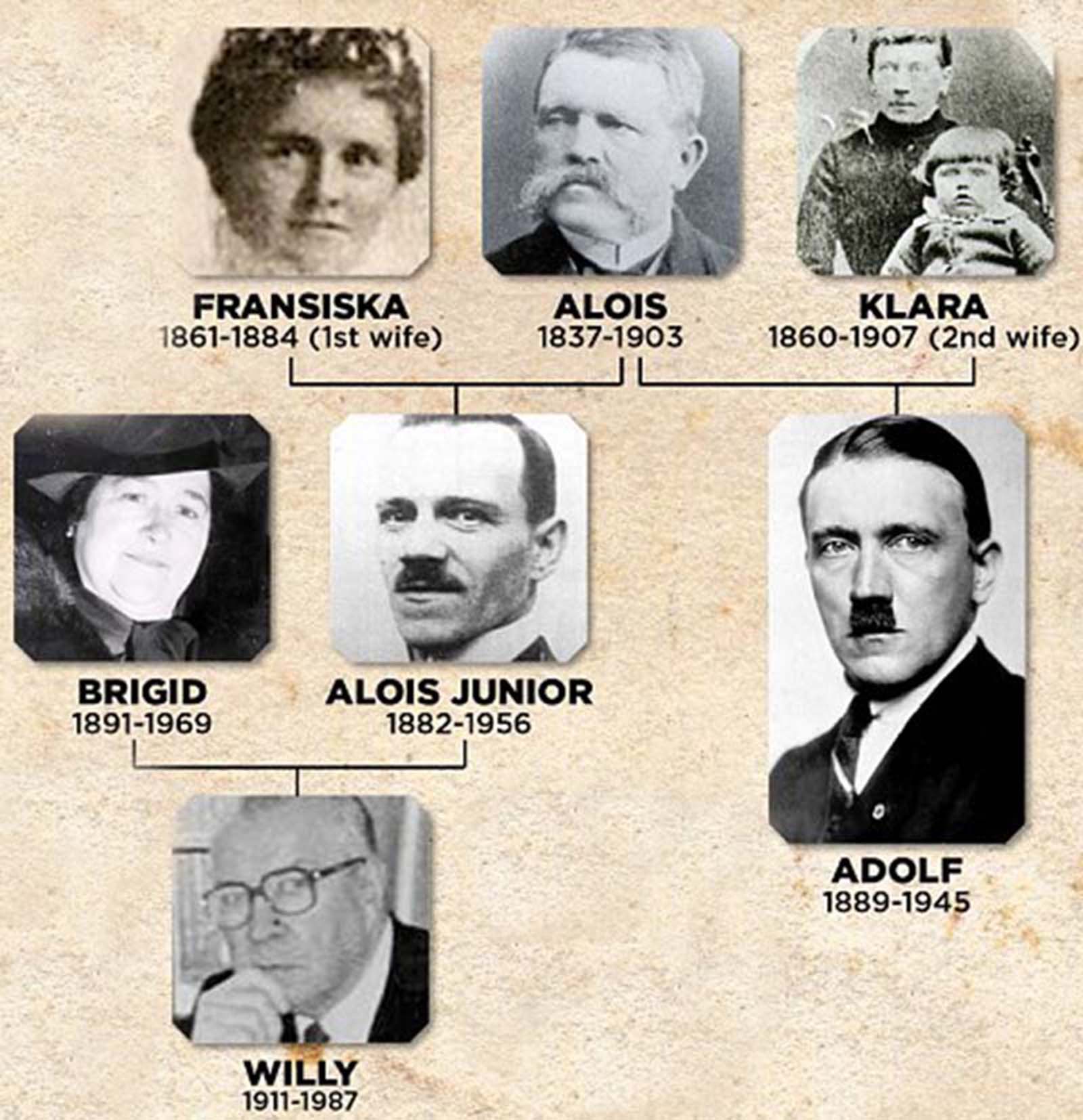

When Hitler’s nephew moved to America and joined the US Navy to fight his uncle, 1911-1947 _ US

William Patrick Hitler, nephew of Adolf Hitler, in his uniform as a member of the US Navy during World War II.

William Patrick Stuart-Houston (né Hitler), son of Alois Hitler Jr, was the half-nephew of Adolf Hitler. He was born in the Toxteth area of Liverpool, England, in 1911, in a house that was, ironically, later destroyed in a German air raid.

Alois Hitler Jr. and Irishwoman Bridget Dowling met in Dublin in 1909 and they married in London’s Marylebone district in 1910 and relocated back to Liverpool.

Alois Hitler left his wife and son in England and moved back to Germany where he started a new family. According to Lyon Air Museum, Willy reconnected with his father when he was 18; he traveled to Germany where his dear old “dad took him to a Nazi rally where he saw his uncle Adolf.” William visited Germany again in 1930, this time meeting his uncle in person and receiving an autographed photo from him.

These happy times with Hitler didn’t last. After returning from a 1931 visit to Germany, William published some articles about his uncle, whose flamboyance and rapid rise to prominence had made him a person of interest to the European and American public.

But, according to William, the Nazi leader didn’t like the way the articles portrayed him. Calling William to Berlin, Hitler reportedly ordered him to retract the article.

William’s 1931 articles about his uncle brought additional unexpected consequences. Now that his relationship to Adolf Hitler was public, William became persona non grata in England. He was fired from his job in 1932. Unable to find other employment in his homeland, he decided to look for work in Germany; perhaps his increasingly influential uncle could be persuaded to help.

In 1933, William returned to what had become Nazi Germany in an attempt to benefit from his half-uncle’s growing power. Adolf, who was now chancellor, found him a job at the Reichskreditbank in Berlin, a job that he held for most of the 1930s.

He later worked at the Opel automobile factory and as a car salesman. Dissatisfied with these jobs, he again asked his half-uncle for a better job, writing to him with blackmail threats of selling embarrassing stories about the family to the newspapers.

In 1938, Adolf asked William to relinquish his British citizenship in exchange for a high-ranking job. Suspecting a trap, William fled Nazi Germany and again tried to blackmail his uncle with threats.

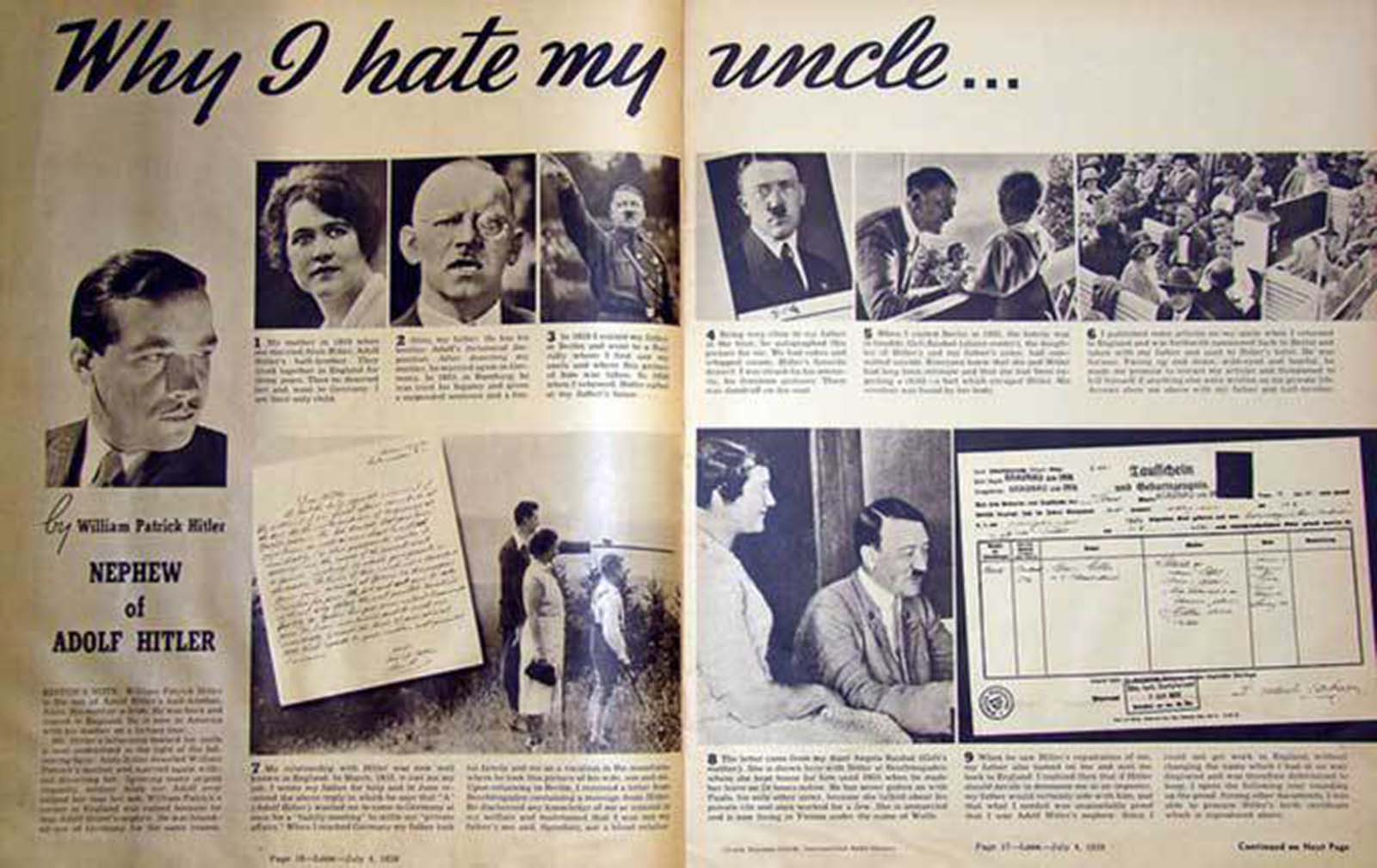

This time, William threatened to tell the press that Adolf’s alleged paternal grandfather was actually a Jewish merchant. He returned to London, where he wrote the article “Why I Hate My Uncle” for Look magazine. He allegedly returned to Germany for a brief period in 1938. It is unknown exactly what William’s role in late-1930s Germany was.

Returning to England, William attempted to join the British armed forces but was rejected because of his direct relation to Adolf Hitler.

So, in February 1939, he embarked for the United States with his mother, eager to share what he had learned about his uncle Adolf and the Nazi regime. He did so during a lecture tour sponsored by newspaperman William Randolph Hearst.

William is sworn into the US Navy by Lieutenant Christian Christofferson in New York City.

After making a special request to President Franklin D. Roosevelt, William was eventually approved to join the United States Navy in 1944; he relocated to the Sunnyside neighborhood of Queens, New York.

William was drafted into the United States Navy during World War II as a pharmacist’s mate (a designation later changed to hospital corpsman) until he was discharged in 1947.

On reporting for duty, the induction officer asked his name. He replied, “Hitler.” Thinking he was joking, the officer replied, “Glad to see you, Hitler. My name’s Hess.” William was wounded in action during the war and awarded the Purple Heart.

Finally tired of the attention his controversial surname attracted, William changed it to Stuart-Houston after returning to the civilian world. He married German-born Phyllis Jean-Jacques, and the couple settled in Patchogue on New York’s Long Island.

William ran a blood analysis lab, Brookhaven Laboratories, in his family’s home. William Stuart-Houston died on July 14, 1987, and was buried next to his late mother in Coram, New York.

Stuart-Houston and his wife had four sons: Alexander Adolf (born 1949), Louis (born 1951), Howard Ronald (1957–1989), and Brian William (born 1965). None of his sons had children of their own.

According to David Gardner, author of the 2001 book The Last of the Hitlers, “They didn’t sign a pact, but what they did is, they talked amongst themselves, talked about the burden they’ve had in the background of their lives, and decided that none of them would marry, none of them would have children. And that’s a pact they’ve kept to this day.”

Though none of Stuart-Houston’s sons had children, his son Alexander, a social worker as of 2002, said that contrary to this speculation, there was no intentional pact to end the Hitler bloodline.

Finally a member of the US Navy, William Patrick Hitler points to “Target Berlin”—capital city of his uncle Adolf’s Nazi Germany—on a wartime poster.

Seaman First Class William Patrick Hitler as he received his discharge from the U. S. Navy.

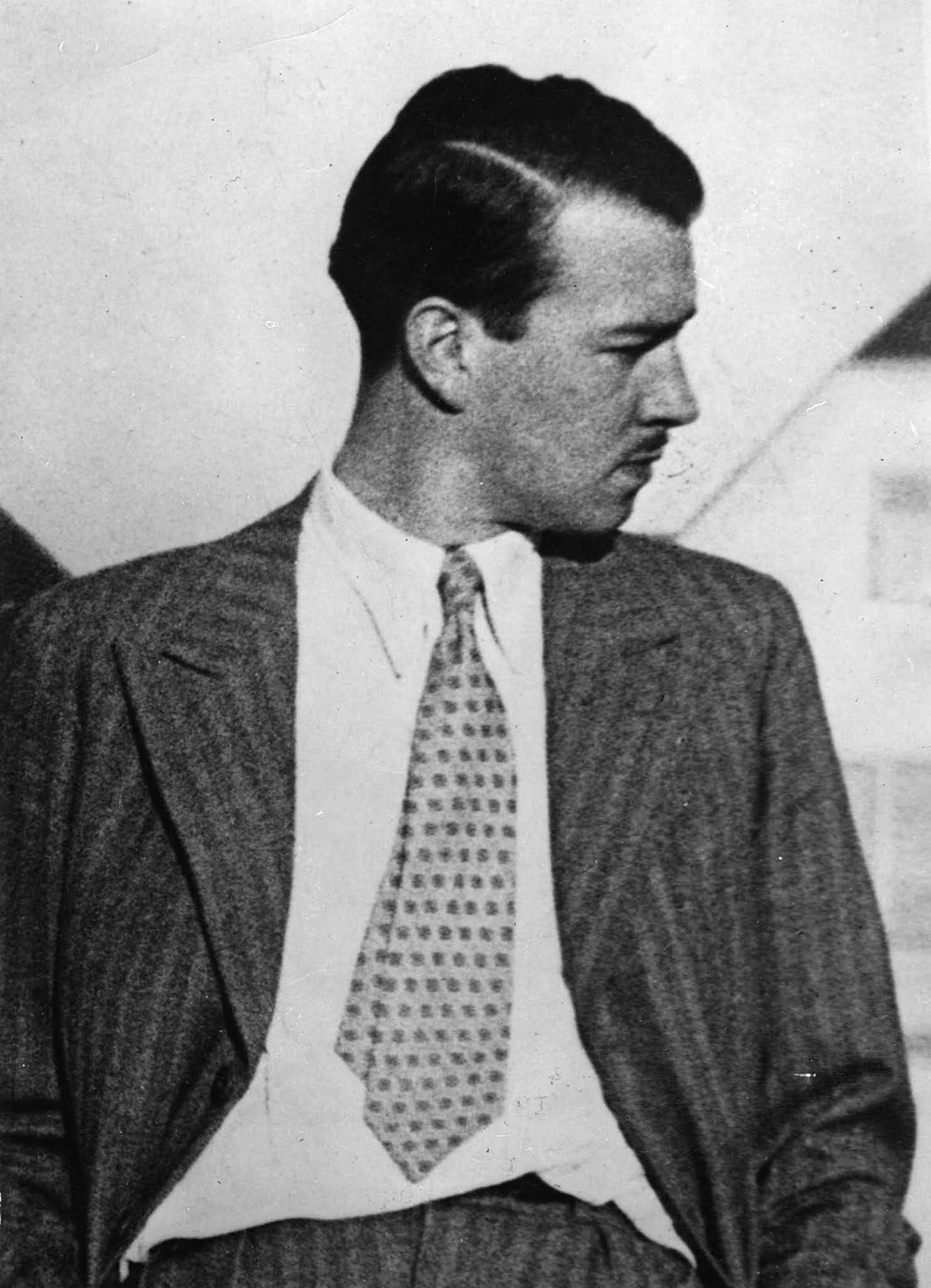

William Hitler, 1937.

William’s mother Bridget stands by him. The newspaper’s title: “To hell with Hitler”.

Front page of a prospectus for the lecture tour.

In the United States in 1941, Bridget Dowling, ex-wife of Adolf Hitler’s brother Alois and mother of William Patrick Hitler, staffs a table promoting help for war-stricken Great Britain through the British War Relief Society.

William Hitler.

William Hitler and his mother.

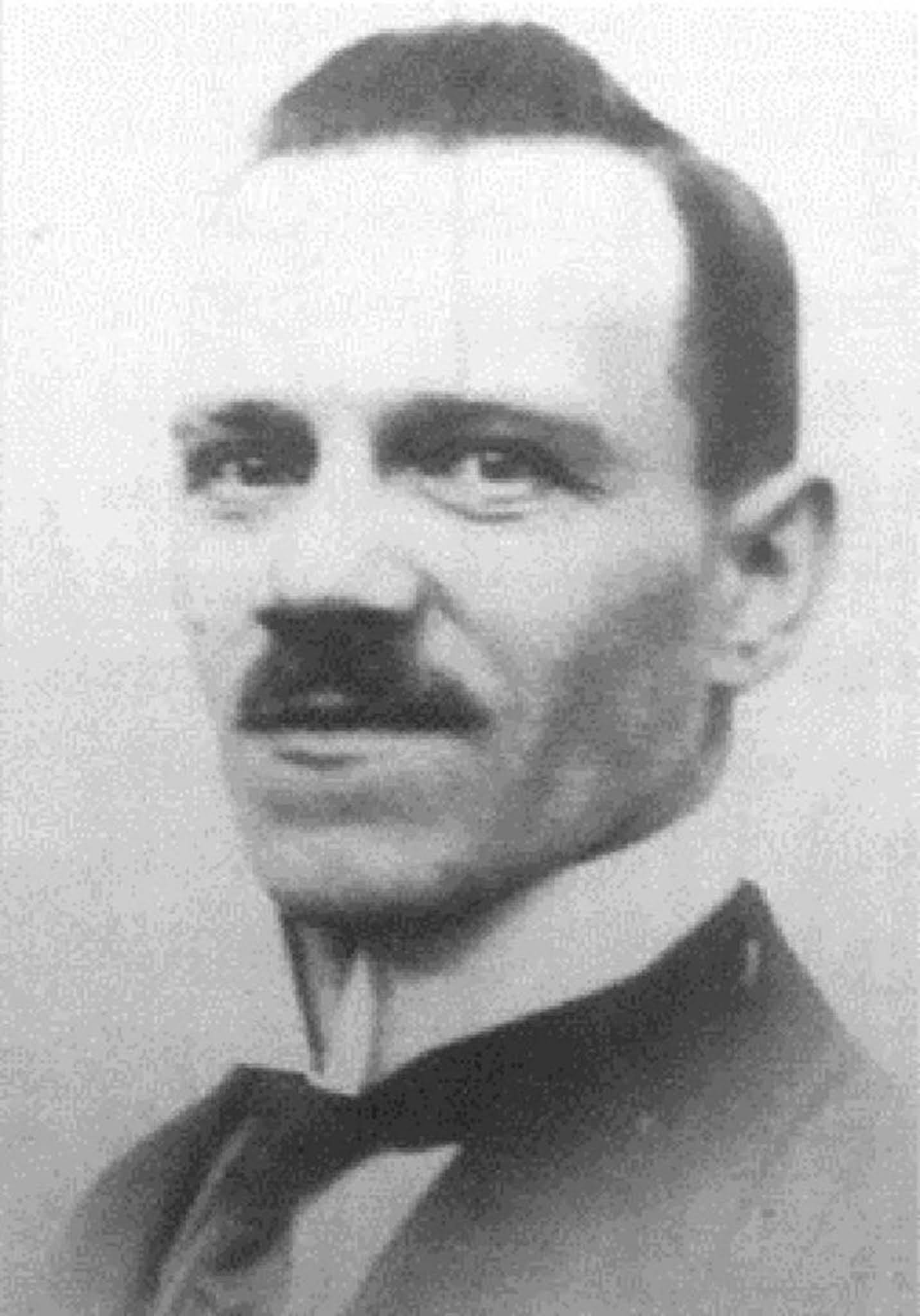

Alois Hitler Jr., William’s father.

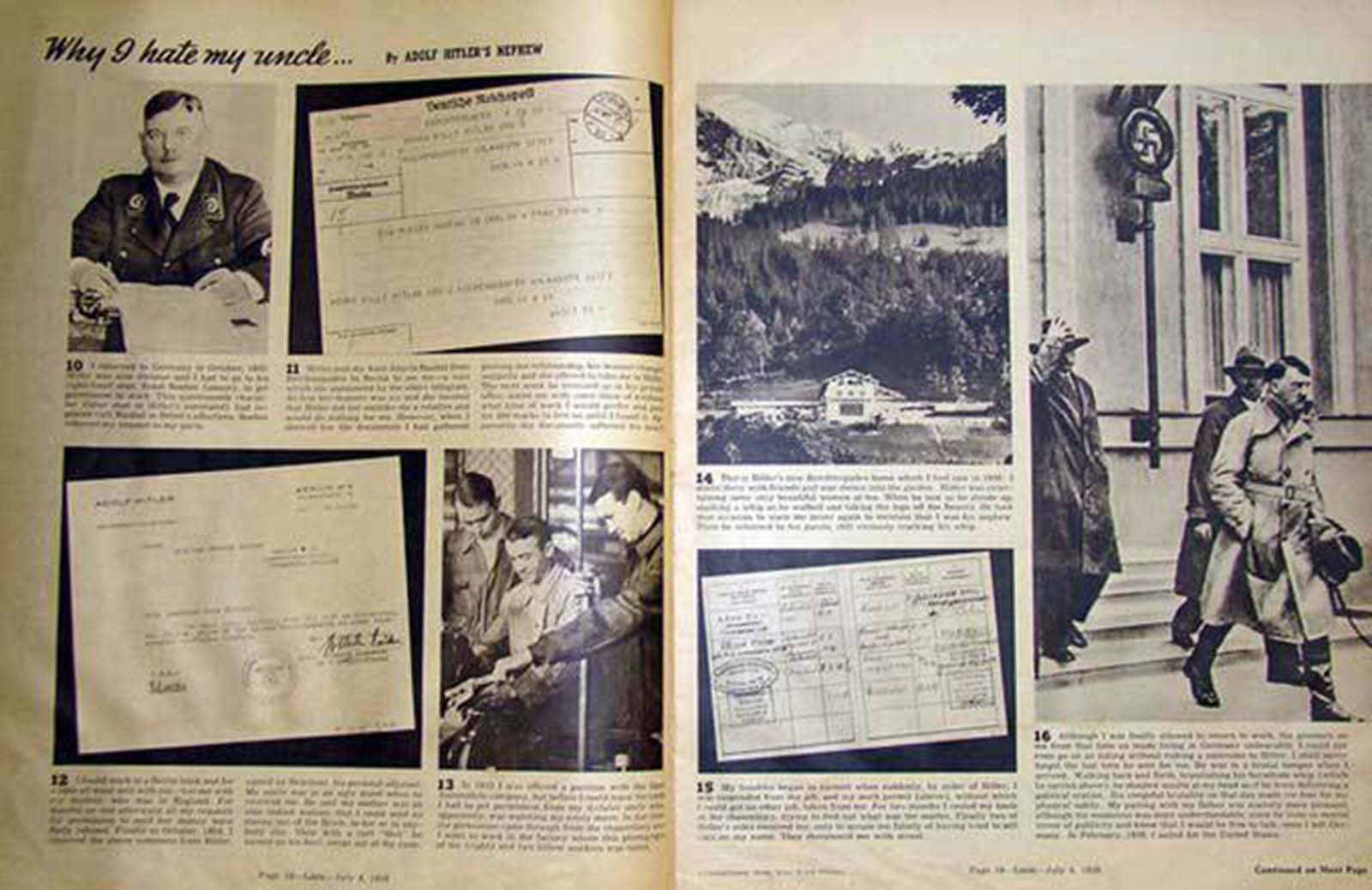

“Why I Hate My Uncle,” by William Hitler (Look magazine, 1939)

Look’s article is written by William and reveals what it was like to be Adolf Hitler’s nephew. Some excerpts are shown below.

“Being very close to my father at the time, he (Adolf Hitler) autographed this picture for me. We had cakes and whipped cream, Hitler’s favorite desert. I was struck by his intensity, his feminine gestures. There was dandruff on his coat.”

“When I visited Berlin in 1931, the family was in trouble. Geli Raubal, the daughter of Hitler’s and my father’s sister, had committed suicide. Everyone knew that Hitler and she had long been intimate and that she had been expecting a child – a fact that enraged Hitler. His revolver was found by her body.”

“I published some articles on my uncle when I returned to England and was forthwith summoned back to Berlin and taken with my father and aunt to Hitler’s hotel. He was furious. Pacing up and down, wild-eyed and tearful, he made me promise to retract my articles and threatened to kill himself if anything else were written on his private life.”

“This is Hitler’s new Berchtesgaden home which I first saw in 1936. I drove there with friends and was shown into the garden. Hitler was entertaining some very beautiful women at tea. When he saw us he strode up, slashing a whip as he walked and taking the tops off the flowers. He took that occasion to warn me to never again mention that I was his nephew. Then he returned to his guests still viciously cracking his whip.”

“I shall never forget the last time he sent for me. He was in a brutal temper when I arrived. Walking back and forth, brandishing his horsehide whip, he shouted insults at my head as if he were delivering a political oration.”

When William Hitler wrote to President Roosevelt

William Patrick Hitler asked to register for military service by writing a fascinating letter (below) sent directly to the U.S. President. It was quickly passed on to the FBI’s director, J. Edgar Hoover, who then investigated Hitler’s nephew and eventually cleared him for service.

March 3rd, 1942.

His Excellency Franklin D. Roosevelt.,

President of the United States of America.

The White House.,

Washington. D.C.

Dear Mr. President:

May I take the liberty of encroaching on your valuable time and that of your staff at the White House? Mindful of the critical days the nation is now passing through, I do so only because the prerogative of your high office alone can decide my difficult and singular situation.

Permit me to outline as briefly as possible the circumstances of my position, the solution of which I feel could so easily be achieved should you feel moved to give your kind intercession and decision.

I am the nephew and only descendant of the ill-famed Chancellor and Leader of Germany who today so despotically seeks to enslave the free and Christian peoples of the globe.

Under your masterful leadership men of all creeds and nationalities are waging desperate war to determine, in the last analysis, whether they shall finally serve and live an ethical society under God or become enslaved by a devilish and pagan regime.

Everybody in the world today must answer to himself which cause they will serve. To free people of deep religious feeling there can be but one answer and one choice, that will sustain them always and to the bitter end.

I am one of many, but I can render service to this great cause and I have a life to give that it may, with the help of all, triumph in the end.

All my relatives and friends soon will be marching for freedom and decency under the Stars and Stripes. For this reason, Mr. President, I am respectfully submitting this petition to you to enquire as to whether I may be allowed to join them in their struggle against tyranny and oppression?

At present this is denied me because when I fled the Reich in 1939 I was a British subject. I came to America with my Irish mother principally to rejoin my relatives here.

At the same time, I was offered a contract to write and lecture in the United States, the pressure of which did not allow me the time to apply for admission under the quota. I had therefore, to come as a visitor.

I have attempted to join the British forces, but my success as a lecturer made me probably one of the best attended political speakers, with police frequently having to control the crowds clamouring for admission in Boston, Chicago and other cities. This elicited from British officials the rather negative invitation to carry on.

The British are an insular people and while they are kind and courteous, it is my impression, rightly or wrongly, that they could not in the long run feel overly cordial or sympathetic towards an individual bearing the name I do.

The great expense the English legal procedure demands in changing my name, is only a possible solution not within my financial means. At the same time I have not been successful in determining whether the Canadian Army would facilitate my entrance into the armed forces.

As things are at the present and lacking any official guidance, I find that to attempt to enlist as a nephew of Hitler is something that requires a strange sort of courage that I am unable to muster, bereft as I am of any classification or official support from any quarter.

As to my integrity, Mr. President, I can only say that it is a matter of record and it compares somewhat to the foresighted spirit with which you, by every ingenuity known to statecraft, wrested from the American Congress those weapons which are today the Nation’s great defense in this crisis.

I can also reflect that in a time of great complacency and ignorance I tried to do those things which as a Christian I knew to be right. As a fugitive from the Gestapo I warned France through the press that Hitler would invade her that year.

The people of England I warned by the same means that the so-called “solution” of Munich was a myth that would bring terrible consequences. On my arrival in America, I at once informed the press that Hitler would lose his Frankenstein on civilization that year. Although nobody paid any attention to what I said, I continued to lecture and write in America.

Now the time for writing and talking has passed and I am mindful only of the great debt my mother and I owe to the United States. More than anything else I would like to see active combat as soon as possible and thereby be accepted by my friends and comrades as one of them in this great struggle for liberty.

Your favorable decision on my appeal alone would ensure that continued benevolent spirit on the part of the American people, which today I feel so much a part of. I most respectfully assure you, Mr. President, that as in the past I would do my utmost in the future to be worthy of the great honor I am seeking through your kind aid, in the sure knowledge that my endeavors on behalf of the great principles of Democracy will at least bear favorable comparison to the activities of many individuals who for so long have been unworthy of the fine privilege of calling themselves Americans.

May I, therefore, venture to hope, Mr. President, that in the turmoil of this vast conflict you will not be moved to reject my appeal for reasons which I am in no way responsible?

For me today there could be no greater honor, Mr. President, to have lived and to have been allowed to serve you, the deliverer of the American people from want, and no greater privilege than to have striven and had a small part in establishing the title you once will bear in posterity as the greatest Emancipator of suffering mankind in political history.

I would be most happy to give any additional information that might be required and I take the liberty of enclosing a circular containing details about myself.

Permit me, Mr. President, to express my heartfelt good wishes for your future health and happiness, coupled with the hope that you may soon lead all men who believe in decency everywhere onward and upward to a glorious victory.

I am,

Very respectfully yours,

Patrick Hitler

(Photo credit: Library of Congress / Wikimedia Commons / War Letters / AmericainWII.com).